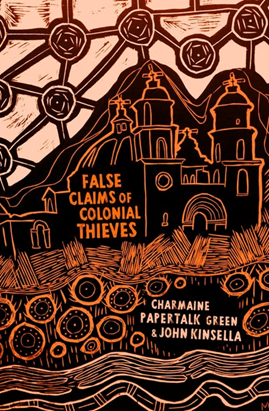

This Resource is for students studying ‘False Claims of Colonial Thieves’ poetry collection by poets John Kinsella and Charmaine Papertalk Green in the Victorian VCE Curriculum.

The Title ‘False Claims of Colonial Thieves’

Refers to the legacy and residue of past wrongs carried out by colonialism that the poets consider were literally ‘colonial thieves’ robbing the Indigenous people of their land under the guise of Terra Nullius [land legally deemed to be unoccupied or uninhabited]. The ‘false claims’ of the title are revealed as colonial misinformation which white-washes the crimes of the past.

The Poets

John Kinsella Born in 1963 in WA is non-Indigenous man who has Anglo-Celtic origins and has written over 30 books based on the WA landscape, colonisation, mining, family and conservation. He supports Indigenous rights, land rights and says he is a ‘vegan anarchist pacifist’. His dedication is to Kim Scott a prize-winning WA Indigenous author of ‘That Deadman Dance’.

Charmaine Papertalk Green Born in 1962 in WA is an Indigenous Yamaji woman who speaks Badimaya and Wajarri. ‘Papertalk’ is her mother’s maiden name. Her message is to restore her ancestors’ histories and stories as ‘paper talks everywhere now’. She exposes the concept of colonisation through her lived experiences and family stories. Her dedication is to her brothers who died to cast relief on Aboriginal mortality rates that are 11.5 years lower than white males.

Both Poets want to know “Who are the real rulers of Australia?”

The collection of poetry identifies itself as political and a serious postcolonial discussion of two poets collaborating to warn of environmental impacts of mining and to track the relationship of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in regards to ‘country’. They both actively interrogate injustices, cultural cruelty, cultural genocide and the pain left behind by colonisation. They seek to challenge the myth of Terra Nullius and rewrite the colonial history of Australia by identifying the colonists not as heroic adventurers into an uninhabited new land, but as plunderers. Through their poems they question the dominant narrative and its instruments of power that fog and irradiate [expose] a land of ‘invisible victims’.

The Ambition of the Collection

The ambition of the collection is the ‘beautiful conversation’ (‘Simply Yarning’ p.97) which is proudly postcolonial; from its title to its references, it invites readers to move beyond the constricting myths of the colonial past and into a more equitable future.

The Structure of the Text

The structure of both the collection and the individual poems is an important part of ‘False Claims’. The collection begins and ends with poems written by the two authors together, ‘Prologue’ by Kinsella and ‘Prologue Response’ by Green which appear on the same page and ‘Epilogue’ which is attributed to the poets jointly. There is thus established a sense of the combined purpose and project of the collection which frames the text, so that even in those sections when there are several poems by one poet, before Kinsella’s voice is again heard, the collaborative nature of the text cannot be forgotten.

‘Prologue’ and ‘Prologue Response’

The repeated language in ‘Prologue’ and ‘Prologue Response’ reinforces the shared project of the poets. This is most clearly apparent in the repeated bitter accusations of negligent ‘environmental scientists’, but it is also evident in the echoed notion of unthinking and unsustainable consumption, appearing in the metaphoric [symbolic] ‘on a platter’ in the first poem, and the more literal ‘plastic bottle’ of the second.

The first poem by Kinsella is longer, the lines are extended, and the text is broken into two verses. The second poem by Green focuses on the obliviousness of the general population raised by Kinsella with the line ‘Stygofauna speak up through the land; some listen, more don’t’ (p.xi). Green repeats the idea of ‘blindness’ through her shorter, more abrupt and accusatory poem, condemning those who refuse to see beyond their ‘privilege’. The structure of these poems, both as they complement each other and as they differ, is a useful reference point for ‘False Claims’. Kinsella and Green share some views, and each poet operates within the context of contemporary poetry, but they are not the same. Green’s poetry is more direct, and her tone is more often angry. Kinsella is more regretful and more likely to consider institutional causes of social and environmental malaise [sickness], rather than referring to personal responsibility.

Language and Style

- Call and response—the whole collection exists as a dialogue between the poets as they negotiate the ‘third space’ of shared understanding. Some of the poems speak directly to each other, and some poems are written in parts, which the poets write in sequence.

- Colloquial (Australian) language (including expletives)—both poets sometimes use recognisably Australian language features in their poems, which creates authenticity in dialogue, and functions to locate the poetry in its Australian regional context.

- Dedications—the collection and some of the poems are committed to the honour of particular people or peoples. Like titles, these dedications can provide insight into the focus and ‘agenda’ of poems and poets.

- Ekphrastic [work of art]—both JK and CPG respond to artworks in poems, a clear knowledge of the artworks (where possible) will assist in understanding these poems.

- Enjambement—when sentences in poems run over lines, a sense of inevitability can be created, either positively or negatively. Both poets use this style feature in some of their poems, and significance of run-on lines should be considered.

- Intertextuality—both poets refer to other texts in some poems, notably in ‘The Wild Colonial Boy’ (pp.135-137 / ‘A White Colonial Boy’ pair (pp.138-140). As well as placing their works into the wider community of poetry and literature, these references indicate the power of texts to shape attitudes.

- Line breaks, stanzas and stanza breaks—indicated with a ‘/’ in quotation, are strategically used by both the poets to create either continuity and flow in poems, or disjointedness and discontinuity.

- Non-Standard English—CPG particularly uses some non-Standard English phrases of spoken Indigenous English, recognising the validity of this patois.

- Pun—the poets, particularly JK, play with words, linking distinct ideas together, challenging assumptions, and creating irony.

- Punctuation / lack of punctuation—JK is strategic in the way he deploys punctuation in some of his poems; reading aloud and following punctuation cues will help recognise the strategic ways in which the poet shapes his longer sentences. CPG often writes without punctuation, depending on rhythm and line breaks to shape the reading experience; this can often create a sense of uncontrolled urgency in her poetry.

- Repetition—both poets use repetition throughout their poetry to create emphasis and sometimes to enhance rhythm; significantly both poets sometimes repeat a line or series of lines from the other poet, indicating their co-operation in the construction of the collection, but also suggesting alternative perspectives to an idea.

- Rhyme—although the poets write largely in free verse, both internal (within a line) and external rhyme (rhyming words at the end of lines) appear in the collection, enhancing or breaking rhythm, associating ideas, creating inevitability.

- Rhythm—poetry is an oral form, so reading poems aloud in class can help students understand the poems, especially when meaning might appear obscure, upon a first (silent) reading. The rhythm of a poem can often become more apparent when poems are read aloud. As with rhyme, rhythm can hold disparate ideas together in a poem, showing the connectedness of different notions. A rhythm can also create urgency, or a mournful tone or a feeling of inevitability, or inescapability, if the rhythm is compelling or almost compulsive.

- Simile, metaphor, personification, symbol, synaesthetic description [figurative language that includes a mixing of senses], alliteration [occurrence of same letter or sound at the beginning of words], sibilance [hissing sound with repetition of ‘s’ sounds]—the poets use various figurative devices which enhance the reach of their poetry, making it more vivid, linking apparently disparate ideas, and evoking landscape.

- Titles—titles of poems, express the way in which a poet directs a reader, from the start of a text. The title of this collection is important as it places all the poems in a postcolonial, revisionist context.

- Use of language—both JK and CPG move into Indigenous languages (Noongar and Wajarri respectively) throughout the collection. This subverts the hegemony [domination] of English and indicates the limitations of English in terms of understanding the subjects the poets write about.

Issues and Themes

The issues and themes are interconnected not only to land, its peoples, cultures, history, stories and art, but the voices of the poets reinforce the connectedness of peoples, stories and histories and the free flowing discussion of the two poets in all the poems in the collection. A commonality between the two poets is the injustice of people and the environment, particularly the destruction of mining, which is not separated in the poems, rather the suffering of both is explored as one country suffering together.

Central Ideas/Issues & Themes Covered in the Collection are:

- Colonisation and Reconciliation

- History and Crimes of the Past

- Redressing Historical Injustices by Reconstructing our Notion of the Past

- The Myth of Terra Nullius (the Colonial Thieves)

- Secrets and Silences of Australian Culture

- History and Memories and their Importance to Individuals

- The Environment and Social Effects of Mining on Country and Individuals

- Exploitation of Mining on Country and Individuals

- Country, Destruction of Country and Landscape

- Family, Friendship, Nature of Loss in Family and Country

- Recognising Important Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Family Members

- Language and Culture of Indigenous People

- Dangers of Cultural Appropriation and Erasure

- The Stolen Generation

- Black Deaths in Custody

- Close the Gap Campaign

- Aboriginal Mortality

- Poetry, Art and the Power of Both

- Racism , Social Justice and Race Relations Between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous People

- Our Responsibility to each other as Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Peoples in Australia

- Social Issues Pertaining to Contemporary Indigenous People

- Stories and Storytelling (Yarning)

Analytical Text Response Topics

- ‘False Claims of Colonial Thieves is more positive about the future than it is negative about the past.’ Discuss.

- ‘Memory is shown to be the most important aspect of culture in this collection.’ To what extent do you agree?

- How do the authors of False Claims of Colonial Thieves show that the natural environment is vulnerable and needs protection in this collection?

- “I won’t pretend it’s easy / Living in an intercultural space” (‘I won’t pretend’, CPG, p.62) ‘Despite the idealism of the collection, False Claims of Colonial Thieves suggests that cultural harmony is impossible.’ Discuss.

- “And the dead are loud in their graves.” (‘Edges of Aridity’, JK, pp.82-4) “Arrived as colonial thieves / Remain as colonial thieves” (‘Always thieves’, CPG, pp.127-8) ‘There is no recovery from colonisation.’ Discuss with reference to the poetry in False Claims of Colonial Thieves.

- How do the poets of False Claims of Colonial Thieves create hope in their collection?

- “How can I but take up the call, / Charmaine, and yarn right back at you – / it’s what we do when we connect” (‘Yarn Response Poem’, JK, p.98) ‘The poems in the False Claims of Colonial Thieves reveal that we are shaped by our relationships with others.’ Discuss.

- ‘The strength of this collection rests in its political agenda.’ To what extent do you agree?

- How do John Kinsella and Charmaine Papertalk Green convince their readers of the healing power of poetry in False Claims of Colonial Thieves?