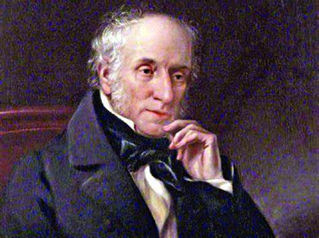

This Resource is for Year 12 students studying William Wordsworth’s Poetry from ‘Poems Selected by Seamus Heaney’ in AOS1, Unit 3: Reading & Responding to Texts in the Mainstream English Curriculum for 2024.

Seamus Heaney’s selection consists largely of the poetry considered to be Wordsworth’s best, written in the decade 1797 to 1807.

Introduction & Themes

Many of Wordsworth’s ideas and values, in the poems in Seamus Heaney’s selection, are concerned with Themes such as:

- our relationship with Nature / life’s circularity / Nature nurtures & wellbeing

- religion / loss and death

- the significance of childhood experiences / wisdom & splendour of childhood / nurturing parents

- family & community / connectivity / wanderers & wandering / humanity & empathy for people less well off in society

- the connection between clear thinking & nourishment of one’s soul in solitude & silence / transcendence

- memory & personal growth / the self & individuality / the power of the human mind

- irrational fear and death / vision / sight / light

- the effects of materialism & industrial change / destructiveness of industrialisation / urbanism

- the pros & cons of political protest / revolutionary activism / rebellion / need for reform

- the problem of social inequality / need for change

Most radically, he viewed natural landscapes as emblematic of the mind of God, and as central to the wellbeing of humans. Wordsworth believed that God was in every aspect of the natural world and so much of his poetry explores nature in a sacred and religious sense presenting goodness and naturalness as synonymous, so nature is a living, divine entity, that if ignored, was at humankind’s peril.

Born in 1770 at Cockermouth on the River Derwent, which is in the Lake District of England, the natural elements of this landscape would come to be immortalised in his poetry. He was a prominent member of the group of poets called ‘Romantics’ that broke the traditional way poetry should be written, believing the poet’s role was to guide others through the transforming power of the poetic imagination.

The Romantic Movement 1798-1832

The Romanticism movement was founded during the Industrial Revolution in 1750 where poets like William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Blake were concerned that people had grown away from nature towards industrial cities and modern mechanisation of mass manufacturing. The Romantic poets had specific ideas that were radical at the time, moving away from traditional poetry, towards breathing imaginative life into all human experiences. Romanticism was an emotional and passionate reaction against the Industrial Revolution, the Age of Enlightenment, urbanisation and its corrosive effects on the individual, community and the landscape.

The Romantics saw landscape and peasant people, ‘folk’ songs and traditions, as representing a simpler time. They regarded the legends, myths and folk traditions of a people as the wellspring of poetry and art, the spiritual source of cultural vitality, creativity and identity. The Romantics agreed with French philosopher and novelist Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s idea that feelings are the human essence, that ‘our sensibility is … prior to our reason’. Abstract reason and scientific knowledge, they said, are insufficient guides to knowledge. Reason and science provide only general principles about nature and people, failing to penetrate to ‘what really matters’, the uniqueness of each person, tree, cloud or lake.

Wordsworth said “all good poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings”. He viewed poetry as being “the image of man and nature”.

Reading Wordsworth poems reveals a poet with a social conscience

One who believes that Nature provides the inspiration for the interior life. He repeatedly returns to the idea of the cycle of life, and expresses both fear and acceptance of death. He looks to Nature for a sense of immortality, although he doesn’t move far from the idea, as in all three ‘religions of the book’, that the earth is infused with, or created by, something beyond the material. Wordsworth was on the side of the ordinary person, and against the authoritarian regimes in power. The theological and social ideas in the poems imply values such as concern for the poor and support for equality and social justice sit alongside the centrality of the individual self. Another interesting element of Wordsworth’s poetry is his presentation of children and how he saw the child as possessing a kind of essential wisdom, allowing them access to truths that were barred to adults. As well as being free from sin, the child was privileged with great insight into the human condition, a gift that was lost in adulthood. Wordsworth suggests that the innocence of children shows us a fresh truth, a new way of seeing.

Nature is central to Wordsworth’s romantic view on life

Writing in an era dominated by the corruptive elements of industrialisation, Wordsworth sought to reinstate Nature as a central focus of human concerns that was increasingly vulnerable. The poet in Seamus Heaney’s collection is Wordsworth himself delighting in the aesthetics found through the environmental grandeur of Nature, presenting it as a source of joy and wonderment. He embraces the language of the ‘common man’ that provokes readers to lament the impact of modernity has had on humanity’s capacity to appreciate natural sensations. For Wordsworth the antidote to the threat posed by the industrial societies that surrounded him lay in the natural world he exalted in both his youth and adulthood. By positioning Nature and by extension, human nature centrally in his poetry, Wordsworth directs individuals to discover deeper truths about themselves and thus humanity as a whole with a focus on the ‘self as subject’. Overall, by concentrating on the sublime [inspirational] elements of the natural landscape, the poet’s collection of childhood epiphanies and philosophical reasonings reveal that immersion in rustic settings is able to guide humanity into a purer state of mind and spirit.

Example Introduction for a Prompt about Grief and Loss

Prompt “How soon my Lucy’s race was run”. While much of Wordsworth’s poetry celebrates the joys of nature and human life, he also focuses on human grief and loss. Discuss.

Use quote in essay “How soon my Lucy’s race was run” = One of the ‘Lucy’ poems “Three years she grew in sun and shower”

Introduction / Main Contention /Message of Poet

Through images and descriptions of the natural world, poet William Wordsworth celebrates the joys of human life, but he is always mindful of the personal elements of grief and loss. By using nature, and men and women within nature, as the inspiration for his imagination, Wordsworth is able to portray a range of human emotions. The complexity of Wordsworth’s poetic vision is apparent when he uses recollections of experiences in the natural world to explore feelings of happiness in living things. In the poem ‘I wandered lonely as a cloud’ the speaker’s joy of his experience seeing daffodils is transposed into an almost spiritual transcendence of his understanding of the joy that nature brings to human life. However, in a natural extension of his poetic sensibility, Wordsworth is able to contrast this joy of life in the natural world with a sense of grief and loss in his series of ‘Lucy’ poems that are seen as a sober meditation on death, grief and loss. Moreover, imagination and memory, Wordsworth suggests, are powerful tools that present the possibility of transcending loss and allow us to gain a more complete understanding and acceptance of human life through nature.

Analytical Text Response Prompts

- How does the poetry in this collection explore the interdependence between humans and the natural environment?

- “The child is father to the Man” How does Wordsworth explore the idea that childhood experiences are significant in shaping the adult life?

- ‘Although the poems show concern for others, they seem more concerned with the self.’ Discuss.

- To what extent does Wordsworth’s poetry suggest that natural rural landscapes must be preserved despite the needs of commerce?

- “… and I grew up/ Fostered alike by beauty and by fear.” ‘Wordsworth’s poetry is animated more by fear than by awe.’ Do you agree?

- “Not without hope we suffer and we mourn” How does Wordsworth’s poetry explore this idea?

- “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive, But to be young was very heaven!” What ideas and values about youth are revealed in this collection of Wordsworth’s poems?

- ‘The poems reveal an ambivalent attitude towards the social changes of the time.’ Discuss.

- “… with an eye made quiet by the power Of harmony, and the deep power of joy, We see into the life of things.” How does Wordsworth’s poetry ‘see into the life of things’?

- “The world is too much with us; late and soon, Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers” ‘The poems in this collection condemn materialism, suggesting that it destroys the life of mind and spirit.’ Discuss.

- “Whither is fled the visionary gleam?” ‘Despite the sense of loss in the poems, the poet more often expresses hope and joy.’ To what extent do you agree?

- ‘Wordsworth shows us that the contemplation of nature can be a way of lightening feelings of melancholy and despondence’. Discuss.

- Wordsworth refers to “a higher power than Fancy”. How does he demonstrate the dynamic power of the imagination in his poems?

- “Ships, towers, domes, theatres and temples lie/Open unto the fields”. ‘Wordsworth successfully marries the contrasting ideas of unfettered nature and the edifices we have constructed’. Discuss.

- “Behold her, single in the field/Yon solitary highland lass”. ‘Wordsworth uses varied images of simple rustics to highlight the heroic and ordinary human life’. Discuss.