This Resource on Key Themes in We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson is for Year 12 Students studying in the Victorian VCE Curriculum.

Family / Domesticity / Power

Jackson’s work reflects concerns about family units and the role of individuals within families, resonating with her own experiences as a daughter, wife, and mother. The Blackwood house foregrounds this focus on domesticity and family, yet Merricat, Constance and Julian undermine the conventional patriarchal structure of a nuclear family. Since Julian is in a wheelchair, he is unable to serve as the conventional patriarch and command the household, instead that responsibility is shouldered by Constance. Merricat is the ‘child’ of the family despite being 18, and is infantilised by Constance.

- Merricat’s attitude towards family might seem to be chaotic and illogical, Jackson’s portrayal of the gendered nature of family life and the tendency for the traditional nuclear family to oppress women gives insight into Merricat’s extreme actions and desires.

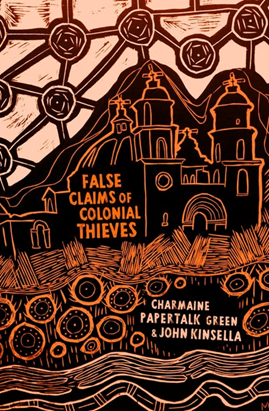

- Male power is especially present in money, as men have traditionally been breadwinners and have used this position to control women. Blackwood men in particular base their identity and success largely on their ability to make money. By entirely disregarding the value of money, Merricat and Constance simply deny the power of men.

- Cousin Charles introduction challenges the established family dynamics and female power of the household. He automatically assumes a position of power, disciplining Merricat and taking control of their father’s room, clothes and patriarchal role.

- Female power in the family and the actions of the female characters reveal a desire for revolt against the patriarchy. Due to family tragedy and social isolation, Merricat and Constance have power over their day-to-day lives that is unusual for young women in the 1960s, and the book is concerned with the sisters’ struggle to defend that power from men who would usurp it.

- Female power and food is where Merricat and Constance rely on feminine power as vested in the traditional female connection to food preparation. In fact, their lives revolve almost entirely around food, and by the end of the book, they spend practically all of their time in the kitchen, with Constance preparing food and Merricat eating it.

Witchcraft / Female Power

Witchcraft historically has been used to undermine female power through demonising unconventional and non-conforming women. There are key historical connections to the Salem Witch Hunt in the 1600’s. While Merricat distances herself from all forms of traditional womanhood, Constance on the other hand depends on it, yet they both have the same fate and are branded as ‘witches’. It is the villagers’ reactions to Constance and Merricat and their capacity for evil that shape our perspective of the girls as witches and victims of a hysterical witch hunt.

- Merricat creates her own brand of witchcraft as she buries protective objects all over the property and decides on words that she believes are powerful. Her cat, Jonas, even acts like her family member, an animal believed to aid witches in their work.

- The demonisation of women is most obvious in the mob’s behaviour towards the sisters. The destruction of the house through fire and the villagers’ throwing of objects mimics the execution of witches by burning or stoning. Except in this instance, Merricat and Constance not only survive the symbolic execution, but find themselves happier than ever after it, as it leaves them entirely out of reach of the male-centric world, with only each other for company.

Paranoia / Fear

Paranoia and fear are a prominent part of the novel, and intersect with wealth, witchcraft, and social exclusion. The Blackwoods are notably paranoid family, guarded about their wealth and the Blackwood men in particular base their identity and success largely on their ability to make money. The Blackwood sisters inherit a similar paranoia, although theirs is directed towards fear of change and an intrusion from outside of their home.

- Jackson uses Charles Blackwood, the sisters’ cousin, to represent the worst of masculinity. He is obsessed with money and he comes to the house with the goal of wringing money out of the sisters under the guise of helping them. He becomes the central danger to the relationship between Merricat and her sister.

- When Charles appears, Merricat detests him with her fear he will disrupt the balance of power in the household by assuming the patriarchal role. It is his striving to lure Constance into a relationship would not only pull her away from Merricat, but would also pull her out of the female-centric world that Merricat has created in their house. Moreover, Merricat’s paranoia of male authority is closely linked with her psychology as her rituals become connected to obsessive compulsive behaviour and reflect an unstable mind.

- Constance’s agoraphobia severely limits her socially and does not allow her to conform to expectations of marriage and society. Since the poisoning of the family and the court case against her, Constance remains the nurturing head of the family and like Merricat at the end of the novel Constance has reached a level of insanity, where her utopia is created from her fears to a state of self-imposed entrapment inside her ‘castle’.

- The anger of the mob against the sisters reveals the nature of paranoia to overthrow people who have not achieved respectability, especially when connoting the witchcraft imagery circulating Merricat and Constance. The villagers exhibit fear and anger towards the sisters, hoping the house will be burnt down and then stone the house smashing everything.

Trauma / Psychology

Merricat is an isolated, estranged hypersensitive young female protagonist, socially maladroit [awkward], highly self-conscious, and disdainful of others. At times she appears more childlike than her 18 years and behaves as if mildly retarded, but only outwardly, inwardly, she is razor sharp in her observations and hyperalert to threats to her wellbeing. Like any mentally damaged person she most fears change in unvarying rituals of her household.

- The trauma and troubled mind associated with Merricat is unclear, Jackson leaves it ambiguous as to what was the motive for her murdering the family. If it was because Merricat was often neglected by her family and sent to bed without dinner, her desire for violence and destruction is about revenge. It could also come down to her psychopathic tendencies and her desire to reject masculine power and the traditional nuclear family.

- Perhaps the trauma was caused to Merricat and Constance they were sexually abused by their father. But the absolute strangeness of Jackson’s novel, and Merricat Blackwood, is rendered glaringly familiar. At the root of it all is an abusive father: Merricat killed the abuser and the rest of the family who allowed the abuse to continue and then she saved her sister and herself.

- Merricat is definitely uncomfortable around men. She is alarmed when Jim Donell approaches her, she detests Charles, perhaps scared that he would inflict the same kind of harm towards her as her father had. Her constant fantasy of living on the ‘moon’ represents an extreme form of escapism in a life free from patriarchal control.

- In the end Constance and Merricat in their solitude appear to resort to insanity they become completely absorbed by one another’s psychological strangeness and never move beyond their paranoid-schizoid thoughts and behaviours, thinking they are happy in their own world.

Truth / Guilt / Punishment

The subjectivity of truth, and the fine line between reality and imagination, is a constant and unanswered question in the novel. Because the story revolves around a mysterious past event, much of the narrative prompts the reader to try to figure out exactly what happened on the fatal night of the poisoning. Throughout the novel, there is a sense that this truth lies just out of sight. For some characters (like the villagers and Uncle Julian), truth is the same as conjecture, and for the two characters that do know the truth (Merricat and Constance), their individual truths never quite line up.

- Merricat’s narration is never reliable. The fact that the murderer narrates the story means that the reader can’t take what she says at face value; instead, one must constantly work to infer what Merricat is leaving out in order to figure out the true story. Furthermore, the reader quickly realises that Merricat isn’t entirely sane, meaning, for example, that she might laugh at something that is actually evidence of her own murderous tendencies.

- What is the truth to the murders? Just like the reader, the characters who don’t know the truth (everyone besides Merricat and Constance) are always working to find the truth or to fight for their version of it. The villagers refuse to believe the outcome of the trial, which found Constance innocent of the murder. Though they might not have the opportunity to accuse Constance to her face, their repetition of a rhyme about Constance poisoning Merricat shows that Constance’s guilt has attained almost mythic proportions among them, regardless of the fact that she’s innocent. Merricat and Constance seem to be the only characters who don’t obsess about the past, in part because they know exactly what happened.

- Uncle Julian is unreliable as a narrator. His love of recounting the night of his own poisoning provides important exposition about the murders. However, the fact that Uncle Julian’s storytelling is the most concrete account of that critical event adds to the impossibility of ever knowing what is true. Uncle Julian is even less reliable than Merricat, as the poison affected his memory.

- Guilt and punishment. This novel revolves around an unsolved crime: the murder of Merricat and Constane’s family six years earlier. While Constance was initially blamed for the poisoning, she was acquitted at her trial, which left the public with no clear answer about who was actually to blame. Meanwhile, Merricat, the real murderer, is never publicly suspected, though, privately, Constance knows Merricat was responsible. The extent to which Constance was complicit in the murder is never fully clear, and, as a result, issues of unresolved guilt and punishment permeate the story, leading to discord among the characters.

Wealth and Class

Wealth and class act as dividers in the novel, exacerbating the isolation and exclusion of the Blackwoods. The house itself symbolises this, being grand, Gothic, and reminiscent of a castle. A key symbol, the house forms the primary setting of the novel, positioned on large grounds, although unkempt, and shut off from the rest of the village. It opposes the houses of the villagers and Mrs Blackwoods drawing room symbolises her obsession with materialism and aestheticism, especially as she did not like to look at ‘commoners’ and instructed the path from the house to be closed off to the villagers.

- Mr Blackwood is obsessed with his own wealth, tracking money people owed him and kept his safe in his study. He controlled his power through money and did not spend money on unessential things and was notoriously miserly with his brother Julian and his sister-in-law Dorothy.

- On the other hand, Merricat and Constance are indifferent to the value of money, only using it to buy necessities from the village. Merricat buries valuable things in the ground, including silver dollars and nails her father’s gold watch chain to a tree. When Charles arrives, and assumes the role of Mr Blackwood, he becomes obsessed about the safe and the value of money, becoming enraged when he finds out how Merricat treats expensive treasures.

- At the end, the house is ruined, all the symbols of power and wealth have been lost. Constance and Merricat are confined to the house and have no need for money at all, receiving food from the villagers and dressing themselves in Julian’s clothes and tablecloths. The house which used to represent class and wealth has been burnt and destroyed and Merricat and Constance break away from the patriarchy along with rejecting class and social status as they relinquish connection with the outside world. Paradoxically, they are free from the suffocating divides of the real world but are prisoners of their own paranoid minds.