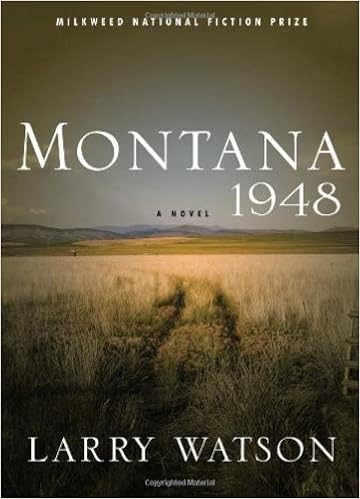

This Resource is for students studying Mainstream English in the Victorian Curriculum the text ‘Montana 1948’ by Larry Watson as a single text or as a comparative text with the play ‘Twelve Angry Men’ by Reginald Rose

AOS1, Unit 2 – Reading and Comparing Texts

Montana 1948 a novel by Larry Watson is a text that can be studied by Year 11 English students in Area of Study 1, Unit 2 – Reading and Comparing Texts. Students are asked to study 2 texts and produce an analytical response to a pair of texts, comparing their presentation of themes, issues and ideas. Students will be asked to investigate how the reader’s understanding of one text is broadened and deepened when considered in relation to another text. Students also explore how features of texts, including structures, conventions and language convey themes, issues and ideas that reflect and explore the world and human experiences, including historical and social contexts.

Comparative Texts – the Novel Montana 1948 by Larry Watson with the Play Twelve Angry Men by Reginald Rose

The most obvious difference in studying/comparing these two texts is that Montana 1948 is a novel and Twelve Angry Men is a play. In a novel the plot is the sequence of events in the text where the characters experience:

- crisis points

- climax

- turning points

- resolution

In a play the acts and scenes are also structured so that the characters are exposed to:

- rising tension

- leading to a climax

- then a resolution

Therefore both forms of text rely on placing credible characters in dramatic situations, often involving conflict, in order to build tension and explore ideas and issues.

Students should pay particular attention to how the authors position their characters in the sequence of events mentioned above and the common thread in the underlying ideas of both texts. Try to choose at least one main specific idea or issue that will allow you to discuss both texts in detail as well as to compare and contrast them. The ideas, issues and themes in a text are what give it wider meaning and relevance. The details of what happens when, where and to whom are all critical, but exist within the world of the text.

Stick to the Themes, Issues and Ideas in the 2 Texts being Studied

A word of warning: stick to the themes, ideas and issues in the 2 texts being studied only. Be discerning using your points of comparison in the analytical text response essay. The context of the text is important but students must work with the ideas represented in the text and the ways authors convey the themes, issues and ideas in these texts. It is not an opportunity to go beyond the ideas in the text or draw into your writing much broader concepts.

What does Theme, Issue and Idea Mean?

- Theme = is the umbrella term for a key focal point in the text

- Issue = takes an angle of that theme

- Idea = presents a point of view on that theme

Texts being studied explore human experience so the themes, issues and ideas then become a vehicle for the human condition in the text and student’s exploration of that. Anchoring the notion of discussion to human experience and what we learn in each text and comparing those texts is important. In order to explore the themes, issues and ideas students might analyse:

- the differences between the narrative voice of a text

- or point of view

- or structural features

- or language features

- or characterisation

- or relationships between characters

- or between different protagonists or antagonists

- drawing on settings and key events that take place

Comparing Texts

When comparing the themes, issues and ideas in the texts, students need to ask “What is the authorial message coming through in the 2 texts? Look at comparing:

- different quotes from each text to look for what words come up in regards to similar themes, issues or ideas

- look at character comparisons, different values, reactions characters make and the different choices made

- scene analysis – compare a key scene or a series of scenes from one text and the other text

- look at tone, imagery and how the author is exploring this

- think of how you would link the above comparisons to a key theme and idea

- consider what ways this changes the way we see the characters, text, reactions and action of them

- How are readers positioned to see the issues in the texts?

In the end of your analysis you need to able to answer the question “How does one text reflect the theme compared to the other text?

Comparing the Central Theme of Achieving Justice in ‘Montana 1948’ and ‘Twelve Angry Men’

In comparing Montana 1948 and Twelve Angry Men an important theme which leads to a common thread of ideas and values is The Importance of Achieving Justice. The central theme in Montana 1948 is whether to choose justice or family loyalty. The central theme in Twelve Angry Men is the importance of a correct verdict that proves the justice system works. A common link between the two texts is prejudice that makes justice difficult to achieve.

‘Montana 1948’ is Set in a Small Town in Montana after WWII

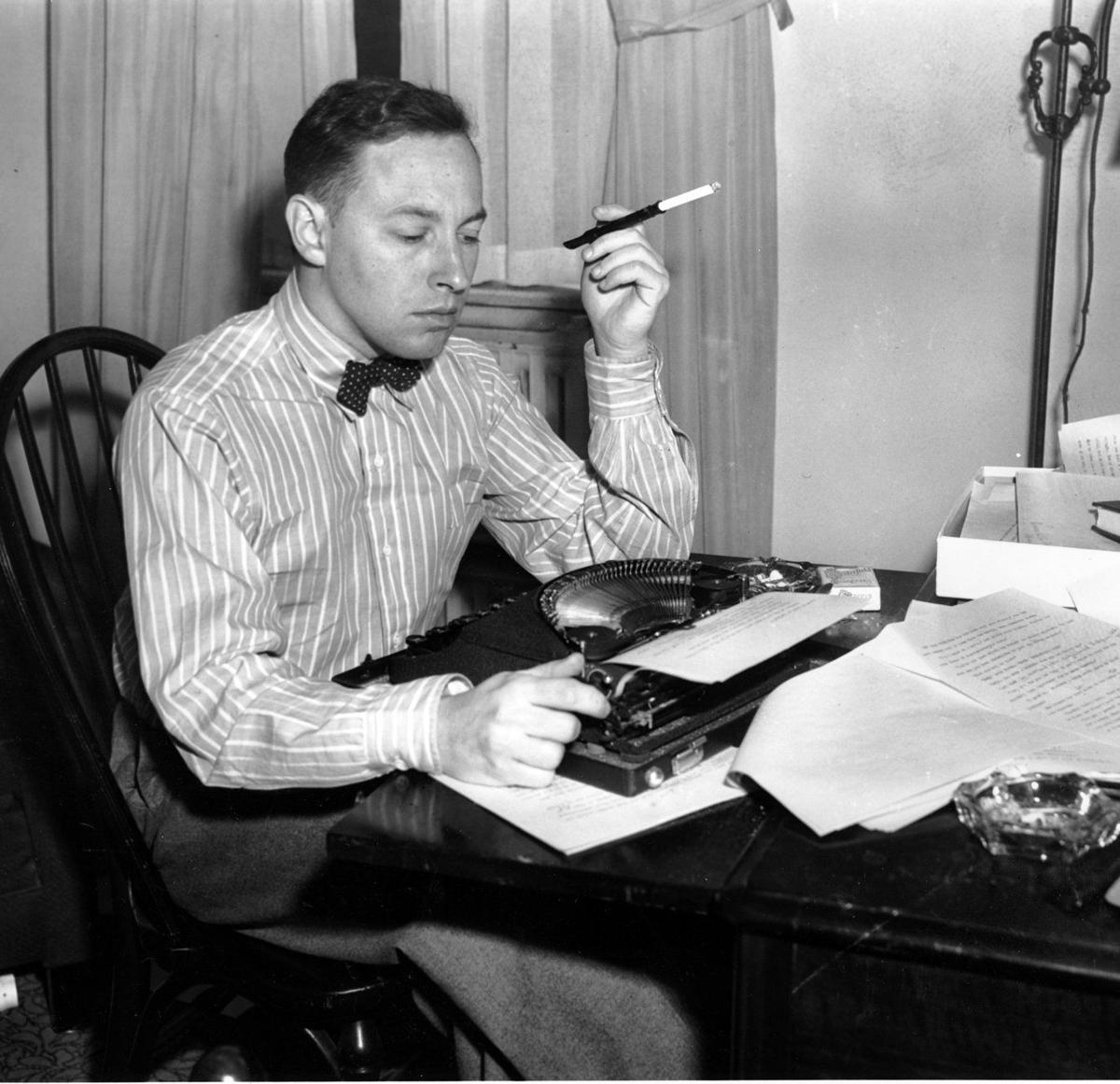

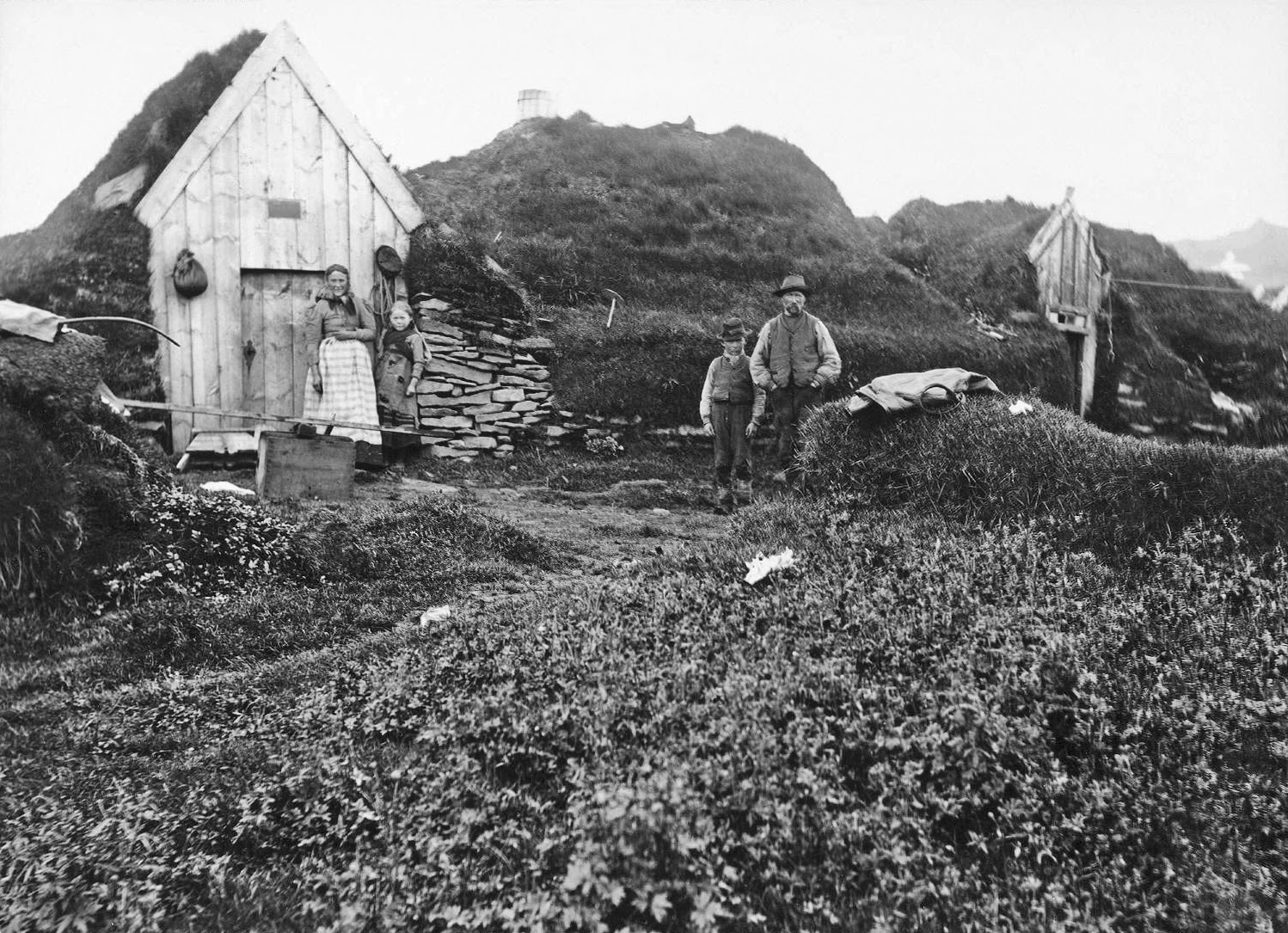

The novel Montana 1948 by Larry Watson is set in a small town in north-eastern Montana in the period just after World War II. Watson drew upon his background in North Dakota with his grandfather and father being the sheriff of Rugby, a small town similar to the fictional Bentrock in Montana 1948. Montana is the 41st State of America close to the border of Canada with its countryside barren and windblown and where cattle and sheep outnumber people by 100 to 1. The significance of the setting of Montana in 1948 is that it is not like the Wild West movies where the Indians wear war paint and ride the plains brandishing spears and tomahawks. Montana in 1948 is where dispossessed Indians are marginalised and are forced to live on reservations outside of town. It is where the white community thought the Indians were useless, non-functioning members of society with their culture not acceptable by white westernised ideas and learning. It is where women were oppressed living subordinate roles in an era before women’s rights were recognised. It is where men have the kind of power that leads to corrupt behaviour which is at the core of Montana 1948.

The Structure & Narrator in ‘Montana 1948’

Montana 1948 is a novel which reconstructs the events of one summer in 1948 in chronological order told by an adult narrator, David Hayden, who recounts events from the perspective of himself as a 12 year old boy and an adult. It is a story of a boy on the threshold of adolescence, awakening to maturity and finding that the adult world is complex and not always fair or just.

The novel is divided into 3 parts with a Prologue and Epilogue. The Prologue foreshadows the action and contributes to the building of suspense before the story begins. The Epilogue closes with the adult narrator summarising the aftermath of the summer of 1948. The action is divided into parts which mark the progression of events and end at a crucial point of development in the story:

- Part One ends with David aware that his father Wesley knows that Frank his brother is guilty of raping defenceless Indian women

- Part Two ends with Wesley’s realisation that now Frank is guilty of murdering Marie Little Soldier

- Part Three ends with the 12 year old David’s naive belief that his uncle’s suicide has solved all outstanding problems

Truth and Justice in ‘Montana 1948’

It is in a setting of racial prejudice that the dark coming of age drama is played out. It tells the story of how 12 year old David Hayden’s uncle is accused of the sexual abuse of Indian women and how the family must choose between loyalty and justice. Characters in the novel find themselves torn between finding and accepting the truth that Frank has sexually assaulted and killed the family maid Marie Little Soldier and then doing what is right. The decision by Sheriff Wesley Hayden to arrest his brother and uphold his duty to serve justice is at odds with protecting Frank and the family’s reputation. In fact truth and justice and acting with moral integrity present choices for the characters in Montana 1948. Each one deals with his/her own conscience in making these decisions.

Wesley’s dilemma of which master he should serve, family or the law is where much of the action of the novel revolves around. Should Wesley be loyal to his family versus justice for a minority group? The question readers need to ask is:- Would the town have reacted differently if the case of sexual assault had been against a white woman?

Gail Hayden is the one person in the novel who maintains the moral high-ground throughout. As a woman in 1948, Gail was on the cutting edge of her society because women were an oppressed powerless group at that time with a low status in society. Gail, however, is an intelligent, non-prejudiced, upright moral citizen who is a positive and protective role model for her family. In fact Gail is the only role model for David who does not appear to be racist towards Indians. The novel clearly shows that no white males in David’s world of Wild West Montana who are without racial prejudice.

Gail’s persuasion of Wesley that Marie Little Soldier has been sexually assaulted by Frank is at the heart of the story. She is the moral fibre that holds Wesley together when he begins to waiver and wrestles with his conscience. She is even willing to protect her family and justice when she waves a shotgun at Julian’s men as they come to set Frank free from the basement.

Complex Themes and Ideas in ‘Montana 1948’

Montana 1948 explores many complex themes that are aligned with particular characters. Below is a list of themes and ideas to help you:

| the importance of family | prejudice | family feuds & disagreements | growing up / adolescence |

| abusing power | justice / injustice | suicide | opinions |

| guilt | sexual harassment | deceit | law and order |

| loyalty | bravery | trust | responsibility |

| racism | innocence | oppression | discrimination |

| truth / lies / secrecy | murder | favouritism | moral integrity |

Is Justice Served?

We wonder whether justice is served at the end of the novel with the family feud. Frank committed suicide to save his reputation, however, Wesley and his family are left behind to deal with the reality of Frank’s actions. They are ostracised by the rest of the family, forced to leave their home and Wesley’s job as Sheriff. The real culprit has died and has been buried with all the honour that a hero would command. Justice has not been served and family loyalty has been compromised. There are no winners or losers when these two issues are opposed.

What Does this Novel Say About Society?

Some thought-provoking questions for students to consider when studying Montana 1948 are:-

- It is better to keep your mouth shut when you know the truth will hurt?

- When do you have to speak out against evil?

- Does justice mean jeopardising your family and future?

- Does power and influence wash you of your crime?

- Should we ignore our moral obligation for a more convenient and easier life?

- Is doing ‘the right thing’ the right thing after all?

- How much does what other people think matter?

- Is it worth it?

- Look at history, are people who stand up for what they believe in rewarded for their efforts, or crucified by the crowd?