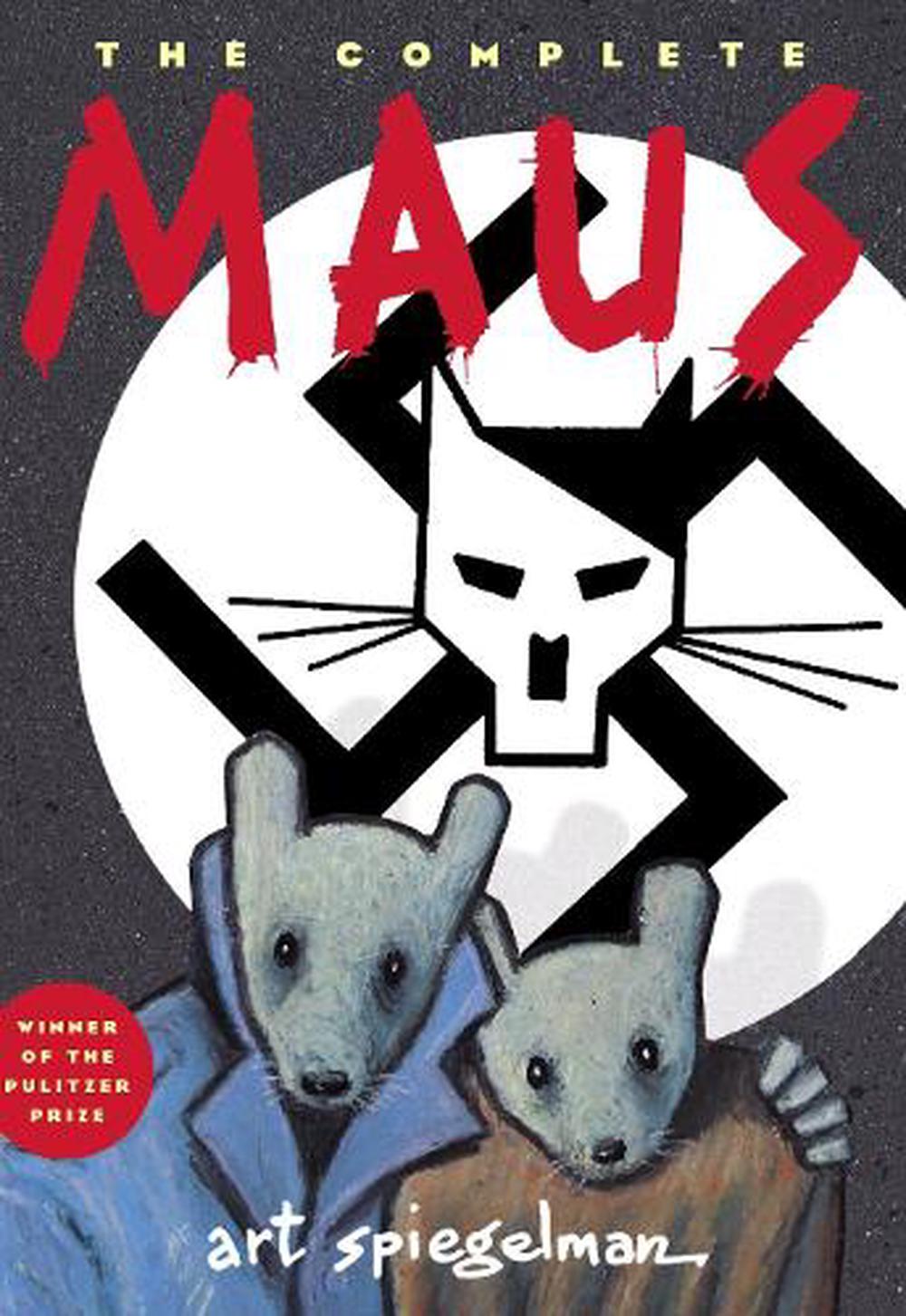

What Genre is Maus?

- It is a graphic novel or actually a graphic memoir since it is a true story. It is a complex story told in pictures and handwritten captions, as opposed to only typeset print. Therefore, it is a piece of visual as well as literary art. By using imagery and limited words, Art Spiegelman has used the art form of cartoons to portray the horrors faced by the Jews as prisoners of the Nazi Regime during World War II.

- It is an oral history and a memoir. An oral history is an extended interview where a witness to historical events is asked to recall what he experienced. Someone else writes it down. A memoir is the story of a life written by the participant or another person. Art Spiegelman interviews his father Vladek between 1972 and 1982 to relate stories of Vladek’s horrific experiences in Nazi Germany during which he survived 10 months in Auschwitz death camp. The stories of the past and present clash and collide so readers also become aware of the difficult relationship between Art and his father.

- It is the story of one concentration camp survivor; a Jewish Polish refugee and his family: Vladek and Anja, and their son Art Spiegelman. Another son Richieu died in the war; so did the other members of Anja’s and Vladek’s families. After Anja’s death Vladek married Mala also a survivor. It addresses the guilt and fear of survivors from the death camps of Auschwitz-Birkenau and the subsequent impact on their children.

- It is the story of a historical genocide known as the Holocaust. The Holocaust is the name for the systematic persecution and murder of 6 million Jews from 1933 to 1944 by the Nazi regime in Germany. In particular the story focus is on Polish Jews.

What is Maus About?

In Maus, Vladek Spiegelman’s story of surviving the Holocaust is told in tandem with the story of his post-war relationship with the author of the book, his son Artie. Although Artie Spiegelman emphasises the resourcefulness of Vladek to survive and his capacity to overcome the dreadful feeling that he was abandoned by God during the Holocaust “But here God didn’t come. We were all on our own” (p.189). Maus is just as much about surviving life after the Holocaust as it is about experiencing the Holocaust itself. Artie says to his wife Francoise towards the end of the book, “But in some ways he didn’t survive” (p.250). Certainly for Vladek the Holocaust was an emotionally crippling experience, reducing him to what Artie says is a “caricature of the miserly old Jew” (p.133) who is concerned more with “things than people” as Mala said. The need to constantly be resourceful and pragmatic had for Vladek overwhelmed other less material approaches to life.

The cartoon graphically relates the Holocaust story and Vladek’s experiences of horror but it is also Artie’s story as a child of a survivor which is at times humorously and poignantly interwoven in with Vladek and Anja’s story. As these stories of the past and present clash and collide, so readers become aware of the pain of broken, disrupted relationships. The second part of the story ‘And Here my Troubles Began’ from pages 169-296 continues the story of Artie’s parents’ incarceration in Auschwitz but also includes more of Artie’s own personal story as he seeks to understand the delayed trauma of an Auschwitz-related son. One of his most pressing points is that the scars are generational ie. the psychological scars of the parents continue to haunt subsequent generations.

An important part of Artie’s story is relaying a snapshot of his father’s post-traumatic stress that suffocates him as he tries to deal with the enormity of his loss. A touch of black humour conveys this depiction, which is both poignant and mocking. Artie ridicules his father’s neurotic obsession with pills and death and his traumatic relationship with his second wife Mala who Vladek imagines her constantly stealing his money.

What is safe to say about Maus is that the graphic images belie the complexity of the psychological pathology that was a result of the Holocaust both for the survivors and the generation that the survivors gave birth to. What is also true in Maus is that the characters, mostly Vladek and Artie, are burdened with feelings that they don’t always understand are often in conflict with each other. If there is a message in Maus it is this: people are complex and nothing is simple.

The Distinctiveness / Techniques /Symbols of Graphic Novels like The Complete Maus

Pages in graphic novels and graphic narratives are made up of words, images and panels. To read them effectively, and to understand their complex and subtle meanings, requires attention to the ways in which both images and words work independently and together. Each has its own logic and way of organising meaning.

One of the things that is important in writing about Maus, is to write about it as a graphic novel. In other words, how does Art use the elements of the graphic novel to tell the story of Maus in a way that is distinctive from the medium of the novel or film?

The Basic Techniques and Symbols Art uses to tell the story are:

- The Panel = Just as the paragraph and sentences within the paragraph are the basic way of dividing up parts of the narrative in a novel, so too is the panel and the speech bubbles the basic way of organising the story in a graphic novel. In Maus Art uses the panels in different ways – with boxed black borders designed to be read from left to right, top to bottom which is a standard way to develop a narrative. The panel boxed within a border conveys the sense that these words, or actions or feelings are happening at this exact point and no other. When there is no border a sense of space or freedom is created – that the words, actions or feelings might link to more than just this point in time. Art also changes the size of panels in order to emphasise the significance or impact of the feelings, words or events within the panel. He does this often at crisis points in the novel such as the arrival of Vladek at Auschwitz. Panels also overlap with other panels to show how words, feelings or events in that panel overlap, impact on or link to the surrounding panels.

- Gutters = The space in between panels – known as the gutter is important – we almost need to ‘read between the lines’ or infer what has happened. In many cases, this doesn’t require much effort, because what is depicted in one panel can come almost directly after what was in the previous panel. Sometimes there is a space between panels in terms of place or time which makes us as readers wonder what happened in between In the scene (p.111) the Gestapo have orders to evacuate Zawiercie where Tosha and the children Bibi, Lonia and Richieu are living but Tosha says “I won’t go to their gas chambers. And my children won’t go to their gas chambers” (p.111). In the scene we do not see Tosha administering the poison to the children but we are left to fill that blank in ourselves based on the image of the small, innocent children looking up.

- Animal Characterisation = Perhaps the most basic and effective technique Spiegelman uses to tell the story of Maus, is the characterisation of Jews as mice, Nazis (and Germans as a whole) as cats, Poles as pigs and Americans as dogs. In this comic story Art utilises this anthropomorphic imagery of the cat and mouse to depict his parent’s experiences in Nazi Germany which also relates the story of the Holocaust. There are a number of layers to this imagery. The first layer is the idea we immediately associate with mice as innocent and small and cats as big, predators of mice. In terms of characters, the Jews were innocent victims; the Nazis were the sinister predatory killers. The second layer involves a subversion of ideas.

- The Language = The story recounted in Vladek’s voice is related in broken English, awkward grammar but giving the impression of spontaneity and authenticity. At times it is extremely sincere but other times it is dramatic but uncaring. Through the language Spiegelman gives his reader a number of cues that can assist in understanding the plot, voice and levels of narrative. It is through the language we are able to comprehend aspects of the characters’ motivations, their relationships with one another and their place in the narrative.

- Eyes = Are a fundamental point of characterisation to humanise or dehumanise characters in graphic texts. The eyes of the Jewish mice are nearly always visible throughout the text and convey the feelings of anger, sadness, frustration or determination. However, the eyes of the Nazis are often not visible; they are shaded by their helmets or caps, signifying how their humanity has been shaded by the role they fulfil. When their eyes are seen they are as sinister looking slits of light.

- Holocaust dominated by Nazi Swastika = Spiegelman represents how over-whelming the Holocaust was in the lives of the Jews who lived through it and survived by his visual representations of Nazi symbols dominating the landscape within panels or being the dominant background behind panels. The panels of pages 34-35 show the swastika prominent in towns even in 1938 in conjunction with texts “This town is Jew Free” (p.35). The panel on page 127 shows Vladek and Anja walking in the direction of Sosnowiec with the path imagery as a swastika. The imagery indicates Vladek and Anja’s predicament of having nowhere to go because in Poland at that time (1944) all paths for Jews led to the Nazis and ultimately to Auschwitz and death.

- Masks = Characters wear masks at two different points in the story. Before Vladek and Anja were captured and sent to Auschwitz, they were able to avoid being caught in Srodula by disguising themselves as Poles (pig masks). Masks at this point are a functional way to avoid detection by pretending to be someone else. In Book II Spiegelman draws himself as a human character wearing a mouse mask which represents his confusion about the suicide of his mother in 1968. He asks questions about why his mother committed suicide. Was it his fault? Why did he feel guilty? How can he move on? Who in fact was he?

- Dying faces, dead faces, hanging and dead bodies = The horror of the Holocaust is reinforced throughout Maus by the graphic representations of the dead and dying. Hanging bodies are used at a number of points with a particular haunting effect. They evoke feelings about the dehumanisation of Jews who were left to hang like carcasses and their powerlessness. Often the dead or dying are portrayed with their mouths wide open, screaming in agony, fear and desperation. The images evoke within the reader a picture of true horror of what the Jews suffered during the Holocaust.

Guilt as a Major Theme in Maus

Guilt swirls in the comic strip. The relationship between Vladek and his son is important in the narrative because it deals extensively with feelings of guilt. Of particular relevance is guilt with members of the Spiegelman family. Artie mocks the fact that Maus should have a message and that everyone should feel ‘forever’ guilty. “My father’s ghost still hangs over me” (p.203). The primary types of familial guilt can be divided into three categories:

- Artie’s feelings of guilt over not being a good son

- Artie’s feelings of guilt over the death of his mother

- Artie’s feelings of guilt regarding the publication of Maus

The second major form of guilt found in Maus is thematically complex. This guilt is ‘survivor’s guilt’ which is found in both Vladek and Artie’s relationships with the Holocaust. Much of Maus revolves around this relationship between past and present and the effects of past events on the lives of those who did not experience them which manifests itself as guilt. While Artie was born in Sweden after the end of World War II both of his parents were survivors of the Holocaust and the event has affected him deeply. Artie reveals his guilt to his wife Francoise “Somehow, I wish I had been in Auschwitz with my parents so I could really know what they lived through! I guess it’s some form of guilt about having an easier life than they did” (p.176).

Vladek too appears to feel a deep sense of guilt about having survived the Holocaust while his family and friends did not. Pavel (Artie’s psychiatrist) thinks that Vladek took his guilt out on Artie the “real survivor”. So Vladek’s guilt was passed down to his son establishing the foundation for the guilt that Artie now feels towards his family and its history.