This Resource is for students studying the play ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ by Tennessee Williams in the Victorian Mainstream English Curriculum

Background to the Play

First performed in 1949, A Streetcar Named Desire sprang from Tennessee Williams’ personal beliefs, reflecting his society as he saw it. In the 1920’s, the American dream of democracy, material prosperity and equality for all had fast disappeared with the Great Depression. This economic crisis began with the 1929 Wall Street Crash, and brought unemployment and great poverty to many. The depression passed, but the idea of such a state of perfection was proved to be unrealistic and unattainable. The characters in the play represent the jaded American dream, and the kind of lives, standards and tensions within which the immigrant population found themselves living.

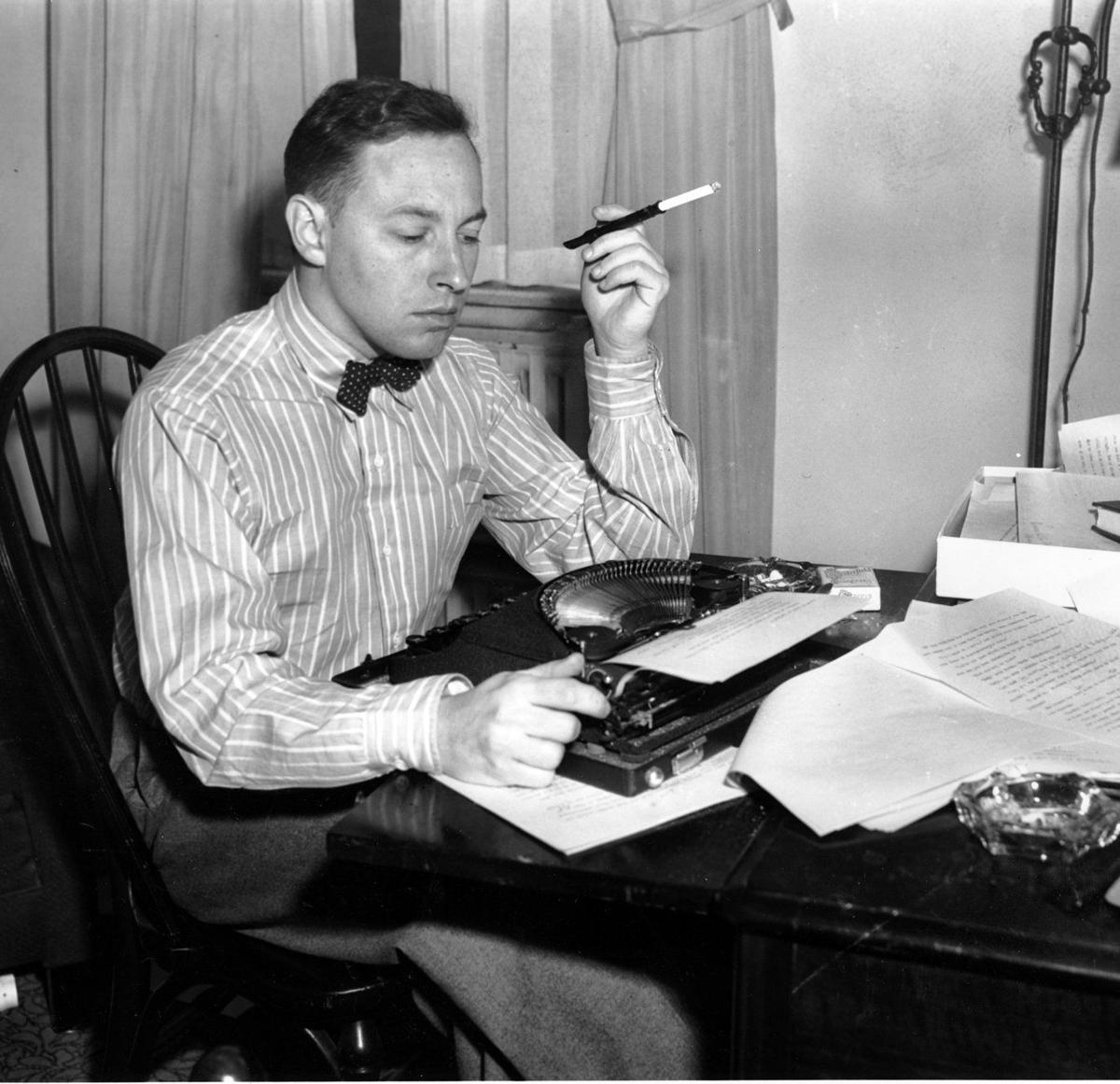

The ‘Forward’ to A Streetcar Named Desire written by Tennessee Williams in March 1959

The ‘Forward’ to the Penguin Books Edition 2000 of the play is written by Tennessee Williams himself and was first published in the New York Times on 8th March 1959. Williams’ own feelings of insecurity and escapism are literally true. At the age of 14 he discovered “…writing as an escape from a world of reality in which I felt acutely uncomfortable. It immediately became my place of retreat, my cave, my refuge”.

Fantasy’s Inability to Overcome Reality

Although Williams’ protagonist in A Streetcar Named Desire is the romantic Blanche DuBois, the play is a work of social realism. Blanche explains to Mitch that she fibs because she refuses to accept the hand fate has dealt her. Lying to herself and to others allows her to make life appear as it should be rather than as it is. Stanley, a practical man firmly grounded in the physical world, disdains Blanche’s fabrications and does everything he can to unravel them. In relation to the Context ‘Whose Reality?’, Williams’ text enables the reader to explore this antagonistic relationship between Blanche and Stanley as a struggle between appearances and reality. It propels the play’s plot and creates an overarching tension.

Through character construction we can see how people like Blanche Dubois are doomed in the world. The play highlights the tragedy of one whose world and whose reality have no relationship with what is real. As the play unfolds the audience witness the destruction of one who craves the abstract notion of love. Blanche represents our desires and our capacity to imagine where we would like to be or how we would like to live. As a direct contrast, Stanley Kowalski epitomises the modern world – pragmatic, cruel, heartless and lacking in sensitivity.

Escapism in A Streetcar Named Desire

Escapism is something we all embrace as a way to unwind and remove ourselves from the hassles of daily life. However, we know we have to face reality and all its complexities. Blanche Dubois’ character suffers one difficulty after another and she is unable to face the harsh realities of her world. Escapism in A Streetcar Named Desire is represented by Blanche Dubois’ character who is unable to face the harsh realities of her world but in the end craves security, love and peace.

When she is raped by Stanley, her ability to distinguish truth from lies and illusion from reality is shattered. Stanley’s declaration before he rapes Blanche, that “We’ve had this date with each other from the beginning!” (Scene 10, p. 215) is a statement of his fundamental need to crush Blanche’s weakness, his “right” to exert his power over her sensitivity. He is the manifestation of a modern and insensitive society that fails to acknowledge those needing support and craving emotional designs rather than materialistic ones. Her rape symbolises society’s inability to tolerate those who fail to fit in to the real world.

Reality Triumphs over Escapism and Fantasy

Though reality triumphs over escapism and fantasy in A Streetcar Named Desire, Williams suggests that fantasy is an important and useful tool. At the end of the play, Blanche’s retreat into her own private fantasies enables her to partially shield herself from reality’s harsh blows. Blanche’s insanity emerges as she retreats fully into herself, leaving the objective world behind in order to avoid accepting reality. In order to escape fully, however, Blanche must come to perceive the exterior world as that which she imagines in her head. Thus, objective reality is not an antidote to Blanche’s fantasy world; rather, Blanche adopts the exterior world to fit her delusions. In both the physical and psychological realms, the boundary between fantasy and reality is permeable. Blanche’s final, deluded happiness suggests that, to some extent, fantasy is a vital force at play in every individual’s experience, despite reality’s inevitable triumph.