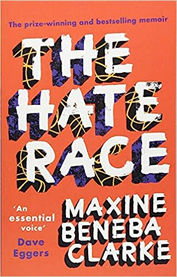

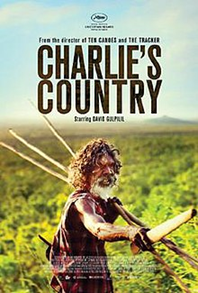

This Resource is for English students studying in the Victorian Curriculum. Racism is an important theme comparison between the memoir ‘The Hate Race’ by Maxine Beneba Clarke and the film ‘Charlie’s Country’ by Rolf de Heer.

Why Compare ‘The Hate Race’ and ‘Charlie’s Country’?

Introduction

Maxine Beneba Clarke’s memoir ‘The Hate Race’ and Rolf de Heer’s film ‘Charlie’s Country’ explore the shifting experiences of racism in Australia. The texts foreground the complex and traumatic impact of racism on individuals, as well as the broader social ramifications of institutionalised racism. Beneba Clarke and de Heer shine a light on the corrosive and unexpected impacts of racism, and the way that this can shape an individual’s experience of the world around them. The texts reveal fundamental truths about the role of racism in contemporary Australia.

A comparison of ‘The Hate Race’ and ‘Charlie’s Country’ offers insight into the common experiences of people of colour, whilst also highlighting the unique experiences of First Nations people. The texts focus on modern day events, dispelling any notions of the elimination of racism in modern Australia. They share a grounding in the historical evolution of racism on both national and global scales. They offer insight into two very distinct geographical locations, again revealing the varied manifestations of both institutional and interpersonal racism.

The pain that is central to the experience of the protagonists in both texts is reflected through the prisms of the memoir and film respectively. Beneba Clarke’s work chronicles the experience of a child through the reflective lens of an adult. Conversely, de Heer’s film showcases the cumulative impact of racism on an adult.

‘The Hate Race’ Memoir is an Autobiographical Work

‘The Hate Race’ is an autobiographical work, a factual yet subjective narrative of events, experiences and emotions from the author’s own life. Specifically, the book is a memoir, since it does not reflect on Clarke’s whole life but on a particular and significant period of it – her childhood. The narrative illuminates how this period would inform the rest of her life (as suggested by the Prologue and Epilogue) when the adult Maxine undergoes experiences intertwined with the discrimination she faced for years as a young person. The book can also be considered a form of bildungsroman or ‘coming of age’ narrative that charts the social, emotional, and psychological growth and development of its protagonist.

‘The Hate Race’ situates the experience of an individual childhood within a broader social landscape. Beneba Clarke’s use of the memoir form allows her to paint a vivid picture of the social and historical forces that shaped the experiences of the author and her family. ‘The Hate Race’ offers an account of an Australian childhood that is distinctly recognisable—a fact that makes the characters’ experiences of racism all the more uncomfortable and undeniable.

The Title ‘The Hate Race’

The title signifies for minorities in Australia, life is constantly akin to a race. There is no rest, no comfort, and no sense of home when your mind is preoccupied with all the ways you don’t belong. Being denied a firm sense of self, and constantly being forced to justify one’s own existence is not easy, and becomes a ‘race against time’ to see who can cope and rise above, and who will be swept away along with the tide. If people of colour stop running, they run the risk of being consumed by the hatred themselves and become so cynical and disillusioned that they forget their culture and accede to the Anglocentric, white majority.

Structure of ‘The Hate Race’

The text follows a largely chronological structure, which has the effect of simulating the cumulative nature of Maxine’s experience of racism. There is an acute sense of the role that racism plays in ensuring childhood and adolescence are experienced differently by children of colour. The carefully placed layers of trauma may not have been fully comprehended by the author as a child, but the adult Beneba Clarke reflects the depth and extent of her wounds through a story told ‘just so’ (p. 3). The chapters of the memoir offer vignettes; seminal moments from Beneba Clarke’s childhood to reflect unflinchingly the toll on a life lived as a person of colour in Australia. Again, as Beneba Clarke notes in the text’s acknowledgements, these memories are about a ‘very specific’ (p. 257) aspect of her life. Racism alone is not her life story, but equally her life story cannot be told without understanding racism.

‘Charlie’s Country’ Film is a Fictional Drama

In contrast to ‘The Hate Race’ which is a factual memoir, ‘Charlie’s Country’ is a fictional drama that incorporates some details from life and some elements of the story that comes from the life of the main actor protagonist Charlie played by David Gulpilil. However, de Heer did not want the film to be interpreted as ‘being about one particular (real) individual’ but rather as ‘being about issues much more widespread, much more representative of many individuals’ (de Heer 2014). In this way, ‘The Hate Race’ and ‘Charlie’s Country’ approach some of their common themes from different directions. While the autobiographical genre of ‘The Hate Race’ concentrates on ideas central to the protagonists’ life, ‘Charlie’s Country’ is more interested in the impact of broad issues on an individual.

Rolf de Heer’s ‘Charlie’s Country’ is a stark, fictional film that adopts many of the hallmarks of documentary filmmaking; this is a film that aims to heighten consciousness about the plight of Aborigines impacted by the Australian Government’s intervention, in 2007, in the Northern Territory. The injustice of institutionalised racism is at the heart of this collaboration between Rolf de Heer and David Gulpilil. Their film focuses on the life of one Aboriginal man, Charlie, whose struggles to find a way to live in the modern world whilst staying true to his cultural identity are constantly thwarted by local, white authority figures.

The Title ‘Charlie’s Country’

The title of the film reflects a simple reality – this is Charlie’s country. Rather than a ‘country’ de Heer speaks of the Indigenous notion of connection to and respect for one’s traditional lands and country. Nurturing this connection is a sacred responsibility and the film reminds us that, despite Charlie’s many trials and tribulations, the land on which he lives is truly his own.

Structure of ‘Charlie’s Country’

The film adopts a chronological structure, tracking Charlie’s decision-making in regards to his attempts to regain meaning and purpose in his life as he tries to return to a more traditional way of relating to his environment. The structure of the film is also circular, Charlie ends up back in the place where he began, and seems in a similar state of something like static, confined despair. There is little sense that his journey has been moving forward, rather the places he finds himself (bush, hospital, prison) seem a series of sideways stumbles with no plan or intention. This echoes Maxine’s journey in ‘The Hate Race’, which begins and ends in the adult Clarke’s life, with matching scenes of discrimination, suggesting that her experiences repeat themselves over and over.

Charlie’s Country can be divided into 3 parts:

- Part 1 – Intervention

- Part 2 – Bush

- Part 3 – Jail

| Common Themes in ‘The Hate Race’ and ‘Charlie’s Country’ | ||

| Racism & bullying | Discrimination– institutional versus interpersonal | Identity – personal and national |

| Prejudice | Growing up black in a white country | Intergenerational disadvantage |

| Belonging | Resilience & resourcefulness | Hopelessness & lack of agency |

| Repression | Gap between generations | Power of language & culture |

| Struggle of being an outsider | Friendship | Trauma & hate |