This Resource is for Mainstream English students studying the film Rear Window Directed by Alfred Hitchcock in the Victorian Curriculum.

Gender Roles, Love & Marriage are important themes that Director Alfred Hitchcock critiques in the film Rear Window. These ideas should be included in essays as evidence of Hitchcock’s views of 1950’s American society.

Gender Roles in the 1950’s

Rear Window reflects the gender stereotypes of the 1950’s in a sexist era before the feminist movement made its mark; both men and women are constrained by cultural expectations and mores [customs & traditions] that were conservative.

Jeff’s own views on women are blinkered and he typecasts many of the women he observes: Miss Torso is viewed as a sexy single blonde / Miss Lonelyhearts as a middle aged spinster / Anna Thorward as a nagging wife.

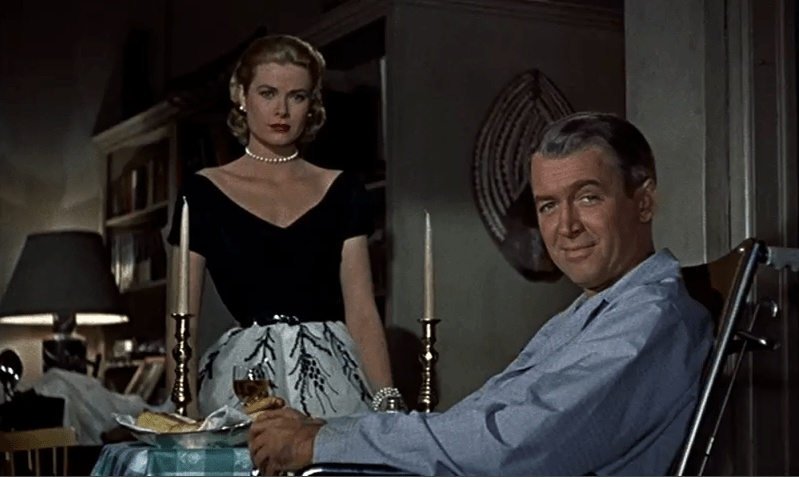

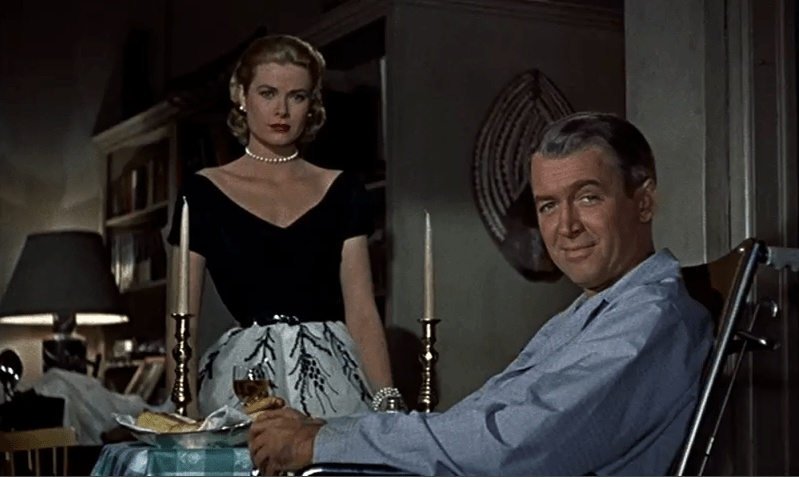

Women are valued for their beauty and physical attributes rather than their skills or intelligence. When Lisa asks how far a woman must go in order to retain a man’s interest, Jeff responds “Well, if she’s pretty enough, she doesn’t have to go anywhere. She just has to ‘be’”.

A beautiful woman like Lisa has to continually fight the perception that her function is essentially decorative and that her value lies in the way she looks, rather than what she thinks, says or does. In this society women are objectified, viewed primarily through the lens of men’s sexual desire.

Gender Divide in Work Men & Women Do

The gender divide is exemplified by the contrasting work that men and women do which reflects a traditional gender bias. Men join the Army or Police; women become nurses or work in fashion. Jeff underrates Lisa’s job in fashion because his work expects an adrenaline rush every time he goes on a new assignment, while working on a fashion magazine as a model and columnist seems mere dabbling in the workforce. The magazine represents the established dichotomy [contrast] between the active masculine role and the more passive feminine role. Jeff’s publication company works for world of news while Lisa’s fashion magazine covers models and submissive women.

Jeff and Lisa’s Gender Dynamics

Hitchcock has the ability to control our “gaze” of Lisa and the attitude he would like us to have towards her. It is apparent through Hitchcock’s Rear Window that he alludes to varying gender norms. Once Jeff is in his wheel chair after the accident, his life remained stable and unchanging in terms of scenery. However, Lisa took on the ability to walk in and out of the apartment as she pleased. This perhaps put a spin on their original relationship when Jeff frequently travelled on various adventures in order to pursue his career as a famous photographer while Lisa remained in her job in New York City. As Lisa tries to convey to Jeff that she can be the jet-setting girl he wants her to be, he frequently denies her that right to even try. He constantly pushes Lisa away and is hesitant to continue their relationship onward. He also pushes her away while he gazes at the window at his various neighbours because she is seen as a distraction.

It is only until Lisa becomes part of that scene and wears the wedding band of the murderer’s wife, that Jeff will accept Lisa as she is and fully accepts that they may soon one day get married. The ring on her finger would symbolically represent Lisa and Jeff’s trust in one another and their changing relationship. The role switch enables Jeff to trust in Lisa that she will always be there for him and he can bring her along on his adventures.

Another way we can see the gender dynamic is through the wardrobe of these two characters. Jeff is constantly wearing his pyjamas and Lisa is the one frequently changing her clothes. She transforms from wearing couture into wearing a pants, suggesting that she must change her appearance in order to please him and the lifestyle that he wants to live. The fact that Lisa works in fashion and cares about her appearance not only shows that she is a woman of class but also one of status and importance. She graciously tries to provide Jeff which a safer and practical job, the exact opposite of his current one, yet he blatantly denies the offer. He acts as if a job in what’s perceived to be a “female dominated” is not good enough for him and also is opposed to the idea of a woman providing him with a job and not the other way around.

The Thorwald Case Casts Lisa in a New Role – Gender Role Reversal

The Thorwald case enables Lisa to successfully transition into Jeff’s domain. A reversal of gender roles follows. Confined to a wheelchair, Jeff has the passive role throughout the drama, while Lisa becomes his ‘legs’ and assumes the more active role, breaking into Thorwald’s apartment to look for evidence.

By subverting conventional male and female roles, the movie challenges the gender stereotyping of the prevailing culture. The lines polarising what men and women can and can’t do have become blurred. With 2 broken legs, Jeff’s emasculation [deprived of masculinity] is so complete by the end of the film that he is no longer in a position to object to Lisa’s presence in his professional life.

Throughout the film, Lisa never loses her femininity, even when she is climbing into a second floor window from a fire escape; she does it in high heels and a floral dress that billows gracefully over the sill. However, in the final scene Lisa is dressed casually in a shirt, jeans and loafers. The message here is that due to her physical activity breaking into Thorwald’s apartment, Jeff sees Lisa differently. In effect Lisa is literally ‘wearing the pants’ in the relationship.

In the past Jeff underestimated Lisa, misrepresenting her as a one dimensional Park Avenue socialite, but since she helped solve the murder mystery and put herself at risk to do so, Lisa demonstrates that women are more than capable of being both feminine and feminist. This is a prescient [prophetic & perceptive] message for Hitchcock to send out to his 1950’s audiences, male and female alike.

Love

To an extent it is possible to see the movie as a film about love in terms of its importance to human beings as well as the catastrophic situations which come about when love fails. It seems that Hitchcock filmed the love scenes like murder scenes and the murder scenes like love scenes. We see this in the ‘kiss scene’ when Jeff becomes aware of Lisa’s presence when her shadow falls ominously over his face, and for one second the sense of threat reigns.

At the beginning of the movie Jeff has two problems, which are intertwined throughout the film, firstly, he has defined his life by impermanence, independence and disconnection and now he is encased literally and metaphorically so that he is stilled, dependent and reliant on others. Second in his relationship with Lisa, this seems to reveal him as both neurotic and childishly frightened of commitment.

The other occupants of the apartments can be seen as representing the various roles available to women, and also the possibilities of love and marriage which Hitchcock depicts as inextricably joined. As Jeff becomes increasing obsessive in his conviction that there has been a murder in the opposite apartment, we look through his eyes into the characters’ personal lives.

It is impossible to avoid the idea that Hitchcock is suggesting that the human need for love and for connectedness to others is essential to our existence. Jeff even objectifies characters as an indication of his own human inadequacy. He uses the clichéd title of Miss Lonelyhearts combined with our position looking from the window across the courtyard controls our response to the pathos [sorrow] of her situation. The film seems to suggest that her life is not worth living without someone to love.

Marriage and Lonely Characters

If Jeff represents the emasculated post-war American man, Hitchcock’s female characters offer a range of possibilities for females in this era, though not necessarily a range of choices. Jeff’s sexist and childish fear of marriage is portrayed by Hitchcock’ as a refusal of life. To a great extent love and marriage go together in this film. Additionally out of this connection comes the idea that however difficult relationships and thus marriages are to maintain, so that they nourish and succour their members, the alternative is so painful that suicide might be the only choice.

Jeff is cynical about marriage is first revealed in the conversation with his editor Gunnison. If Lisa regards marriage as a partnership one that involves sharing and companionship, Jeff views it as a trap. Buried under his resistance is an element of guilt. He knows that Lisa loves him and a part of him also knows that it is unfair to string her along. However, using his career as the excuse for avoiding commitment, he would prefer to keep the relationship as it is. In weighing up his options, Jeff finds that his views on marriage are influenced by what he observes.

The Thorwalds mirror Jeff and Lisa. There is a superficial resemblance between the two women and each relationship has reached a crisis point. Mrs Thorwald and Lisa are also linked by their handbags and by the wedding ring. For Lisa the ring is a symbol of success, of knowledge achieved, and of hope for her own marriage. However it is also an ironic reminder of the failed marriage and the complete erasure of Mrs Thorwald.

Hitchcock also suggests that the newlyweds are on the way to a marriage like the Thorwalds. They are consumed by their sexual pleasure but by the end of the film are beginning to bicker. The film hints that there is more to understand about Miss Torso than Jeff’s reductive label conveys. The comical entrance of her husband Stanley reminds us that looks are not everything. Miss Lonelyhearts suffering is very real. Hitchcock makes it clear that her problem is the lack of love, synonymous with marriage. She is so lonely that she creates a fantasy dinner party guest, and she needs to drink to give her courage to go out in search of a man.

The composer is another lonely person. His attempt to compose his song is a thematic connector through the movie. Hitchcock links his unsatisfactory personal life with his frustrated professional life. It is his song, finally completed, that saves Miss Lonelyhearts and brings him success. Hitchcock hints at the possibility of a relationship between Miss Lonelyhearts and the composer with the song giving her a reason to live. She says “I can’t tell you what this music has meant to me”. He smiles fondly at her.

The movie ends with domestic justice – Thorwald is sent to jail, Miss Lonelyhearts finds a companion in the composer. Lisa metaphorically lets her hair down for Jeff by wearing jeans and attempts to read an adventure book. Both of the surviving women have reached their peak happiness in the prospect of marriage and both are seen in their male partner’s apartment, thus conforming to the man’s life instead of their own. With the final scene, Hitchcock imprisons the women in their endless quest to please men, with no indication of further ambitions or further capacities.

OR think of an alternative perspective on women (in particular Lisa) that Hitchcock has given viewers to consider. Why does Lisa put down the book on ‘The High Himalayas’ and picks up ‘Harper’s Bazaar’? Has she just won the gender race? Lisa is quite capable of being both feminine and a feminist. By subverting conventional male and female roles, Hitchcock challenges the gender stereotyping of the prevailing culture and sends a message to his 1950’s audiences ‘not to underestimate women’.

All Resources created by englishtutorlessons.com.au Online Tutoring using Zoom for Mainstream English Students in the Victorian Curriculum

For Mainstream English students studying the film Rear Window Directed by Alfred Hitchcock in the Victorian Curriculum. See below some of the suspense scenes along with film techniques to help when you write your Analytical Response Essays.

For Mainstream English students studying the film Rear Window Directed by Alfred Hitchcock in the Victorian Curriculum. See below some of the suspense scenes along with film techniques to help when you write your Analytical Response Essays.