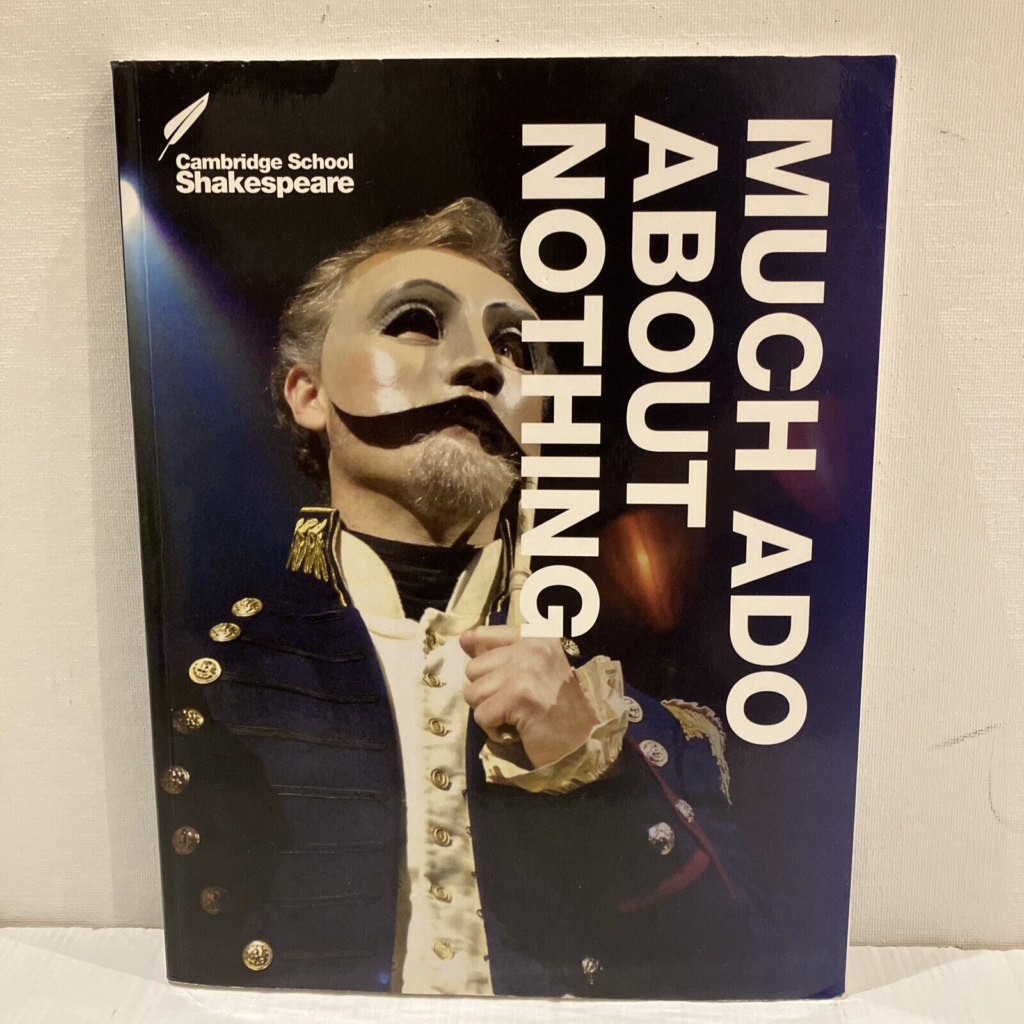

This Resource is for students studying ‘Much Ado About Nothing’ play by William Shakespeare in Analytical Text Response, in the Victorian VCE Mainstream English Curriculum

Human Emotion and Psychology

Usually classified as a romantic comedy, William Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing is both a love story and a ‘much darker and stranger play’ (Dobson 2011/The Guardian). The play is a study in human behaviour, of psychological power and abuse; it is a critique of social structures; it hides some of the ugliness of human behaviour behind a veil of light comedy, ambiguity and fast-paced wit.

In the process of all of this, the plot of Much Ado About Nothing also just happens to include two budding romances built on the tenuous grounds of perception and deception. In exploring human emotion and psychology, Shakespeare draws ambiguous connections between love and loathing, desire and distrust, union and destruction, honesty and deception, trust and doubt, malice and forgiveness. Shakespeare’s pairing of antithetical themes in Much Ado About Nothing highlights how people can be inconsistent in their approach to relationships and romantic unions, deceiving themselves as well as others.

The Fatal Flaw

Much Ado About Nothing also explores desire, and people’s need for reciprocal love; how we respond when we believe we have attained love, and how we rail at our (sometimes perceived) rejection. Shakespeare’s contrast of the relationship between Hero and Claudio with that of Beatrice and Benedick suggests that genuine affection only comes from seeing your partner as a whole person: flawed, the product of their environment or context, and with strengths and charms. Many of Shakespeare’s characters have this ‘fatal flaw’, a defect in their personality, that taken to extreme, can lead to their downfall. Each character has their own ‘fatal flaw’ that shines light on some of the darker characteristics of humanity.

Marriage According to Beatrice & Benedick

Beatrice and Benedick do not simply revile marriage for the sake of being contrarians; such a justification would be disappointing in otherwise complex and interesting characters. They are older and they lack the social status of other characters such as Hero and Claudio; they see the absence of meaning in life and therefore in marriage, yet they enjoy the cut and thrust of their intelligent witticisms. They understand that marriage does not augment their enjoyment of life or contribute to some greater existential meaning.

That Shakespeare’s characters, at times unknowingly, make much ado about nothing perhaps reflects the playwright’s view that life is ultimately pointless. Benedick’s conclusive justification for requiting Beatrice’s alleged love is that ‘the world must be peopled’ (II.iii.p.61), and the song of Balthasar ‘Sigh no more, ladies, sigh no more’ exhorts the ladies merely to: … be you blithe and bonny, Converting all your sounds of woe, Into hey nonny nonny (II.iii.p.53). The song addresses the main manipulators of trickery and deceit, the men.

Perspective of the Text – Romantic or Cynic?

Beatrice & Benedick

There are two broad ways of experiencing Much Ado About Nothing: as the romantic and as the cynic [sceptic]. One need not wholly subscribe to only one or the other. Looking at the 2 relationships, it is easy to view Hero and Claudio in a cynical manner and for Beatrice and Benedick, a more romantic view. Beatrice and Benedick’s love is so pure because it comes without the baggage of inheritance and class, and the false notions of romance which conceal obligation. Their cutting remarks have stripped each other and they have nothing left to hide. Beatrice gives as good as she gets when it comes to the sort of male banter Benedick engages in. Here is a couple who will argue, they will not grind their lives away under the deceptively heavy shade of pleasantries and a false concern for the other’s feelings which in truth is used simply to avoid conflict; Benedick and Beatrice need not fear conflict, they thrive off it.

Claudio & Hero

Interpretations of the values and attitudes surrounding the relationship between Claudio and Hero are much more ambiguous. Given that ‘Shakespeare takes shape through our interpretations’, how do we interpret the easy susceptibility of the Count, the Prince and the Governor to the malignant trickery of the Prince’s ‘bastard brother’ Don John? One interpretation is that Claudio’s behaviour is unforgivably unacceptable. (For a contemporary #MeToo audience, so he gets off far too lightly). Another is that it is patriarchal social values that are at fault, and another that the fault lies with codes of masculinity in which male bonding is cemented with misogynist jokes and banter.

Or perhaps the shocking metaphorical ‘death’ of Hero is generated by the ‘comedy’ of mistaken perception, and we forgive the gentlemen their bad behaviour because the near-tragedy is a plot device, a structural necessity of the romantic comedy genre. However, no reading of the play can excuse the brutality of [Claudio’s] treatment of Hero, but the conventional comic action does demand that he be forgiven.

Title of the Play

The title of the play is open to various interpretations. The most straightforward explanation; that much ado is made over allegations that hold nothing of the truth, suggests the play is a comment on people’s rash judgment and disproportionate responses, particularly to gossip. This relates to the interpretation which replaces ‘Nothing’ in the title with ‘Noting’, a near homophone and colloquialism for ‘noticing’ or ‘gossip’, which connects the title to both pairs of lovers: Beatrice and Benedick base their conscious acceptance of their feelings on overheard misinformation, and Claudio is twice deceived by the snake-like whisperings of Don John, comments that the play is ‘most appositely titled’ because of its reference to the ‘nothingness’ of life.

Style of the Play – Comedy or Tragedy?

While all stories, even comedic ones, need some kind of complication and climax, Shakespeare certainly puts the drama in dramatic structure. He heightens the climax of Much Ado About Nothing to the point where it could have toppled into tragedy. This sets the play apart in the world of comedy, as the stakes are so high and dire circumstance so nearly realised; though it begins and ends with merry wit, there are dark issues explored as the life-threatening action of the play takes place.

Analytical Text Prompts

- What role do deceptions play in Much Ado About Nothing?

- How does Shakespeare present love and marriage in the play?

- In Act 2, Scene 1 (p.43) “Come, you shake the head”. How does Shakespeare present Don Pedro in this extract and elsewhere in the play?

- How does a modern context affect our interpretation of the Hero-Claudio relationship?

- “I will assume thy part in some disguise/ And tell fair Hero I am Claudio” (i.i.p.17 Don Pedro). We accept the deceptions in the play because mostly the characters’ intentions are benign. To what extent do you agree?

- How does Shakespeare use comedy in Much Ado About Nothing to explore serious themes and values?

- “… yet sinned I not/ But in mistaking.” Forgiveness is too freely given in Much Ado About Nothing. Discuss.

- Much Ado About Nothing is a joyful play which celebrates human relationships. Do you agree?

- The women in Much Ado About Nothing are the true holders of power. Discuss.

- Shakespeare’s characters hide their insecurities behind innuendo and metaphor. Discuss with reference to at least three characters in Much Ado About Nothing.

- Don John is the only example of authenticity in Much Ado About Nothing; all the other characters wear masks of some sort, at some time in the play. Do you agree?

- “I speak not like a dotard, nor a fool/ As under privilege of age to brag” (v.i.p.133 Leonato). It is their privilege that makes the behaviour of characters in Much Ado About Nothing all the more reprehensible. Discuss.

- Much Ado About Nothing is supposedly a comedy but the play contains many darker, more tragic elements than a typical comedy. In what ways is this play tragic?

- A central theme in the play is trickery or deceit, whether for good or evil purposes. How does deceit function in the world of the play, and how does it help the play comment on theatre in general?

- Language in Much Ado About Nothing often takes the form of brutality and violence. “She speaks poniards, and every word stabs,” complains Benedick of Beatrice (II.i.p.37). What does the proliferation of all this violent language signify in the play and the world outside it?

- In some ways, Don Pedro is the most elusive character in the play. Why would Shakespeare create a character like Don Pedro for his comedy about romantic misunderstandings?

- In this play, accusations of unchaste and untrustworthy behaviour can be just as damaging to a woman’s honour as such behaviour itself. What could Shakespeare be saying about the difference between male and female honour?’