This Resource is for Year 10-11 Students studying ‘Burial Rites’ by Hannah Kent in the Mainstream English Victorian Curriculum

All page numbers referenced in this analysis of Burial Rites by Hannah Kent are taken from the Picador edition published in 2014 (as shown on the front cover above).

Genre of Burial Rites

Primarily a historical novel, the narrative was inspired by the true story of the last women Agnes Magnusdottir to be executed in 19th century Iceland. As in the book, Agnes was convicted in 1829 and beheaded in 1830 for the murders of Natan Ketilsson and Petur Jonsson. Hannah Kent called her novel a ‘speculative biography’ in that she has used what is known of Agnes’ life and presented a possible version of the truth.

Agnes’ fate is a foregone conclusion but the key question running through Kent’s text is that of Agnes’ guilt. In this regard Kent does build up sympathy for Agnes and allows the reader to explore some mitigating circumstances of which the authorities at the time were ignorant or indifferent.

Post-Modernist Structure of Burial Rites

Kent adopts a post-modernist structure and framework of the narrative which follows primarily the last six months of Agnes’ life with the period of time she is held in custody at Kornsa. The novel commences in March 1828 immediately after the murders but moves to Toti’s appointment as Agnes’ spiritual guide the following June. It concludes with Agnes’ execution in January 1830. Within this framework Agnes recalls the events that led up to the murders. There are thirteen chapters which are book-ended by a short prologue and an epilogue that provides the last official word on Agnes’ execution.

Kent includes official historical texts about the trial and execution that depict the inflexible administration of justice. Official documents are juxtaposed against diverse texts, excerpts from Icelandic sagas, contemporary poems and the compelling first person narrative of Agnes, which seems to speak for the under-privileged and homeless people of Iceland.

So like many postmodernist texts, there is a perspective from the point of view of the powerless that exposes the cruelty and hypocrisy of the powerful. The setting of the novel is an immediate source of fascination, as we know so little about Iceland. Kent economically creates a frozen world, with its harsh beauty and isolation from the rest of Europe. Through Agnes’s eyes we feel the struggle to survive in 19th century Iceland, where fish skins substituted for glass windows.

Language of Burial Rites

Kent’s prose is designed to complement the historical documents that preface each chapter with language that is appropriate to both the historical and geographical setting of the novel. Her language is rich and coveys a rural 19th century sensibility, while remaining accessible to modern readers. Kent frequently uses earthy similes such as: “Even as the light flees this country like a whipped dog.’’ (p.247), which sounds authentic to the modern ear. She gives a poetic voice to Agnes’s reflections: “We’re all shipwrecked. All beached in a peat bag of poverty.’’ (p.248)

At times nature is personified and the novel contains striking descriptions of the harsh elements that the people of Iceland had to deal with on a daily basis. Agnes describes the highland blizzards and seasons as “Winter comes like a punch in the dark” (p.70). In chapter 13 Agnes is close to the end of her life and knows the harsh wind “will scrape you up under its nails and take you out to sea in a wild screaming of snow” (p.319).

Convincing Characters in Burial Rites

Kent populates her novel with convincing characters but it is the character of Agnes that Kent explores with a deft touch. She is neither presented as an object of pity nor even of righteous indignation. Agnes’ inner strength and intelligence is noted by several characters, but it is a strength which is hard won. Agnes speaks how the authorities do not know her “I am determined to close myself to the world, to tighten my heart and hold onto what has been stolen from me” (p.29). Agnes articulates a determined struggle to hold onto a private sense of self despite cruel social labelling. “They will not be able to keep my words for themselves. They will see whore, the madwoman, the murderess, the female dripping blood on the grass and laughing with her mouth choked with dirt … But they will not see me” (p.30).

This novel tries to reach Agnes in a place of terrible loneliness, something that is achieved to a considerable extent through Agnes’ relationship with Margret, the wife of the District Officer who is required to accommodate Agnes. At first, Margret is initially distraught at the idea of Agnes coming to stay at Kornsa as she does not want the safety of her two daughters compromised by the presence of a notorious criminal. When Margret sees Agnes she is outraged by the woman’s condition and insists on the removal of Agnes’ handcuffs so that she can be thoroughly washed. Margret makes it clear to Agnes she must work for her keep as she has no use for “a criminal, only a servant” (p.62). Agnes wants to shake her head and say out loud “Criminal, that word does not belong to me, I want to say. It doesn’t fit me or who I am” (p.62). The slow thawing of the relationship between Margret and Agnes is handled superbly and becomes the mainstay of the novel.

The Significance of the Title

Burial rites in a conventional sense is a ritual or ceremony performed after death but in Agnes’ case the title suggests a rite of passage as a preparation for death. Agnes goes on a figurative journey that involves reclaiming her worth as an individual at least in the eyes of the Jonsson family with whom she establishes a connection. Sharing her story with the family at Kornsa and with Toti affords Agnes a kind of catharsis and the bonds forged between them help her to meet her death with some dignity.

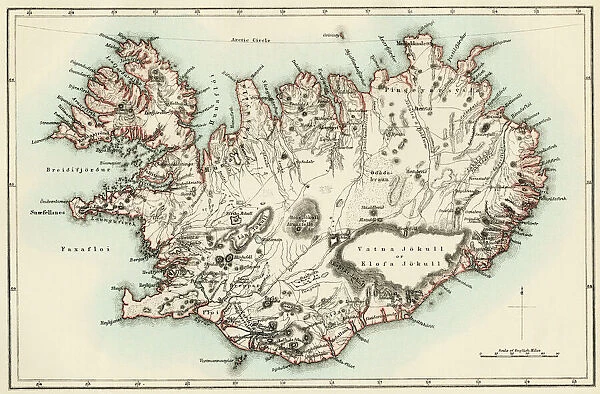

The Historical Setting of 19th Century Iceland

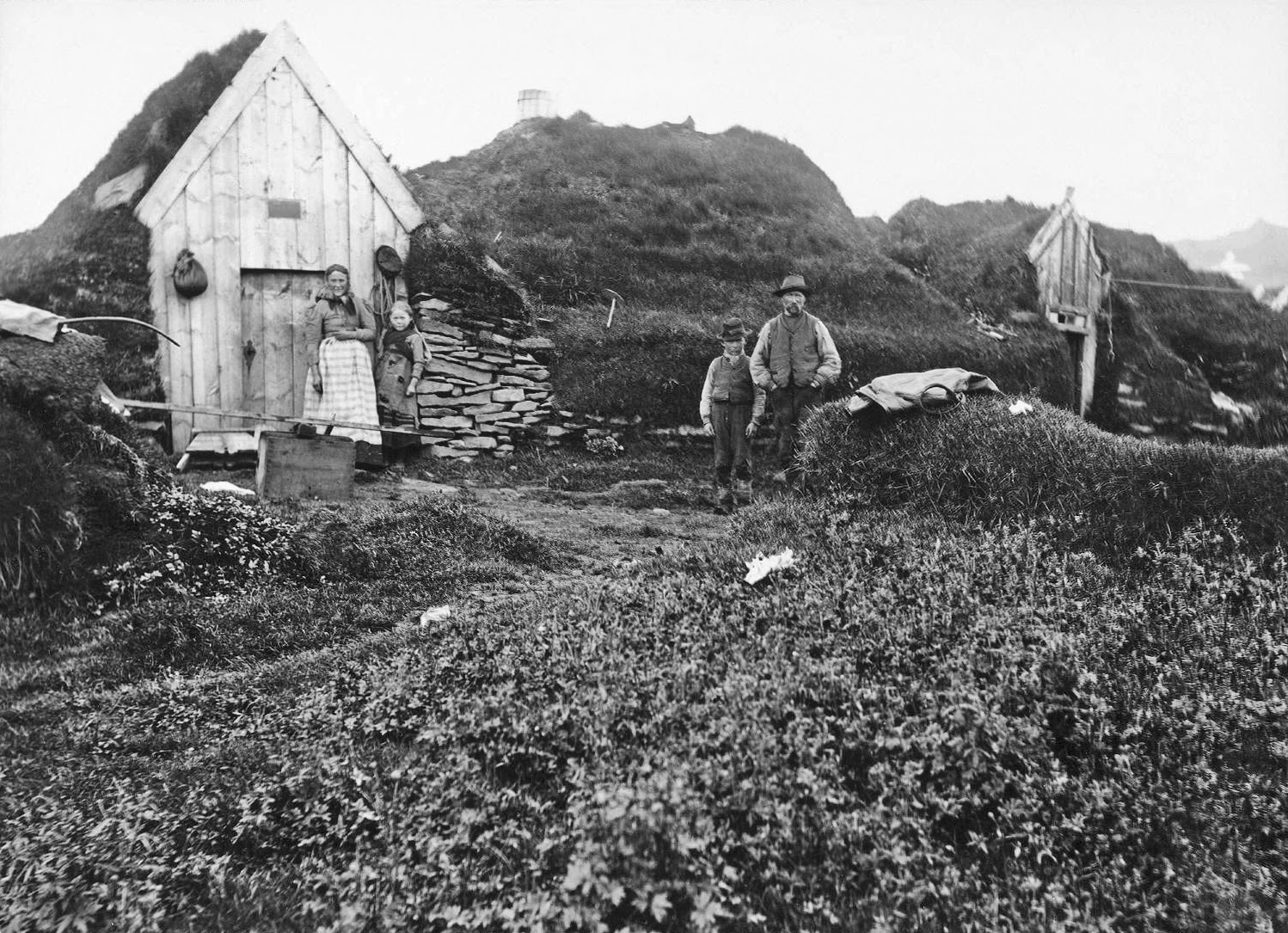

Iceland in the 19th century was a colony of Denmark and ruled by the Danish monarchy. It was deeply divided by class with land titles concentrated in the hands of a relative few. The bulk of the society was agrarian at which farmers produced enough food for themselves and their families but life was a tenuous existence. The society was conservative dominated by a religious ethos and traditional gender expectations. The peasants lived in turf houses that were made up of small crowded rooms with exposed turf walls that were dank and mouldy in the winter infesting the lungs of those who lived there. In the novel Margret’s fragile health is probably due to TB which is a lung condition common from breathing the dust inside her house.

The Landscape and Weather of Iceland

Arguably, the landscape and the weather it spawns is the most powerful force in the novel, shaping days and deciding destinies for the Icelanders who live with such a restrictive climate. In fact the weather’s impact is unavoidable. Literally everything from burials to executions is contingent upon the weather. Simultaneously harsh and beautiful the landscape in this novel is almost a character in its own right.

Kent describes the Icelandic landscape as one that shaped both the body and soul of those who have to fight against it for a living. It is not a place of much warmth. Chapter 6 is where Agnes tells the story of one of the most harrowing sequences in the novel. Agnes’ foster-mother, Inga, dies giving birth, partly because a blizzard is so bad that it is literally impossible to get out of the house, let alone raise the cry for help. As a result the body of Inga’s stillborn child is put in the storeroom as the remains of Inga herself are likewise stored until the ground thaws enough to allow a burial. The weather adds further horror to Agnes’ narrative and we read of the terrifying image of a dead Inga lying kept “like butchered meat, drying in the stale air” (p.157).

The Odds are Stacked Against Poor Women

Burial Rites demonstrates that for poor women there were few choices. Female servants were subject to their master’s will and society’s gender expectations were narrow. Women were expected to know their place in social hierarchy and poverty made women even more vulnerable. In Agnes’ case, Kent’s novel doesn’t take the easy way and blame a cruel God. Human agencies are at work, such as hypocritical treatment of children and single women, and a very flawed criminal justice system. Hypocrisy is evident in Blondal’s self-serving rationalisation of his selection of Natan’s brother, Gumundur Ketilsson, as the executioner. Indeed this historical novel shows the odds are stacked heavily against poor women.

Themes, Issues and Ideas in Burial Rites

- Truth and Stories = Burial Rites is a fictional recreation of history that is presented by Kent as Agnes Magnusdottir’s story. Kent can only speculate on the truth and her interpretation allows for the possibility of Agnes’ guilt or as we readers obtain a version of the original story, we can make our own minds up. The novel questions the idea of truth as an absolute. We obtain the facts as to what Agnes tells us and she shares with us what she chooses to tell us.

- Women’s Roles = Women had few opportunities in 19th century Iceland and their roles were confined to the domestic with some status and respectability through marriage. Poverty made women even more vulnerable and created the double standard where women are seen as promiscuous but men are not. Agnes mother Ingeldur is judged as a ‘loose’ women and had three children to all different fathers from farms around the valley as she tried to find work and a refuge for her family. Unfortunately the price she had to pay was often another pregnancy and a new mouth to feed. Agnes later experiences similar exploitation.

- Authority and Control = Maintaining law and order in Iceland was dependant on a punitive approach of the ruling Danish authorities. Bjorn Blondal as the District Commission has to keep control of the ‘corruption and ungodliness’ that the murders at Illugastadir represent. As a convicted prisoner Agnes is clearly disenfranchised by the law but she is also dehumanised by a brutal system that identifies her as being on the bottom rung of a rigid social structure. Chained like an animal and denied light and air she has been reduced to the status of a beast. Presented to the world and branded a ‘criminal’ Agnes is a shamed outcast.

- Love = Kent presents love as a damaging emotion that inflicts misery and uncertainty and even destroys lives. The epigram “I was worst to the one I loved best” from the Laxdaela Saga at the beginning of the novel sets the tone for what is to follow. Unfortunately Agnes loves someone who is a notorious womaniser. Natan lacks a moral compass in his selfish treatment of Agnes and Sigga. Regrettably Agnes loves Natan and tolerates his appalling treatment of her because she has nowhere else to go and her loneliness makes her vulnerable. Once Natan feels suffocated by Agnes he ends the relationship. Looking back Agnes has to admit that the idea of love can be closely allied to hate. In chapter 11 when Natan throws Agnes out of the house in the snow it underscores his cruel nature but also the power dynamic between them that would never be an equal one.

- Loss = Loss in 19th century Iceland is clearly related to the harsh rural life under constant threat by the inhospitable weather. People are conditioned to accept loss as many infants die and women also die in childbirth. Agnes realises after her foster-mother Inga dies that life brings little certainty. When she is condemned to death Agnes is threatened with another kind of loss that compounds her dread. She fears the loss of her personal identity, a loss of self. Agnes’ final monologue reveals the extent of this terror. Denied Christian burial rites she feels that death will bring no permanent resting place. She will be lost and her memory will vanish into oblivion.

- Redemption = As a Lutheran Minister Toti’s duty is to help Agnes atone for her sins and save her soul. Blondal’s interest in Agnes is less about the state of her soul than in containing a sensitive political issue. The execution is really an exercise in propaganda as it is in the law’s interests to be seen as God’s instrument. In reality Agnes’ salvation comes not from the unforgiving approach of the law but from being treated with fairness and compassion by the family at Kornsa. Agnes connection to Toti is also central to this process of redemption. At the end Agnes’ guilt or innocence becomes of less important than the faith that Toti and the family at Kornsa have in her. Being drawn into the loving circle of those around her is Agnes true redemption. As Agnes is taken to be executed Margret pressed her fingers tightly to Agnes and said “We’ll remember you, Agnes” (p.324).